Howard Hughes: his extraordinary life from high-flyer to hermit

The troubled billionaire

Who wants to be a billionaire? We might dream of extreme wealth, but the fate of America’s once-richest man suggests it can have damaging consequences.

Howard Hughes seemed to have it all: mountains of money, myriad talents and movie star looks. Yet he died an emaciated recluse, hiding away from a world he couldn’t trust and consumed by the same obsessive personality that drove him to succeed in everything from aviation to the film industry.

Read on to learn about the extraordinary life and legacy of Howard Hughes, one of America’s most enigmatic figures.

All dollar amounts in US dollars.

Humble origins

Howard Robard Hughes Jr. was born in the town of Humble, Texas on Christmas Eve 1905. At least, that’s what a birth certificate claimed; a baptism certificate said he was born three months earlier and didn’t give a location. In any case, young Howard’s upbringing was anything but humble.

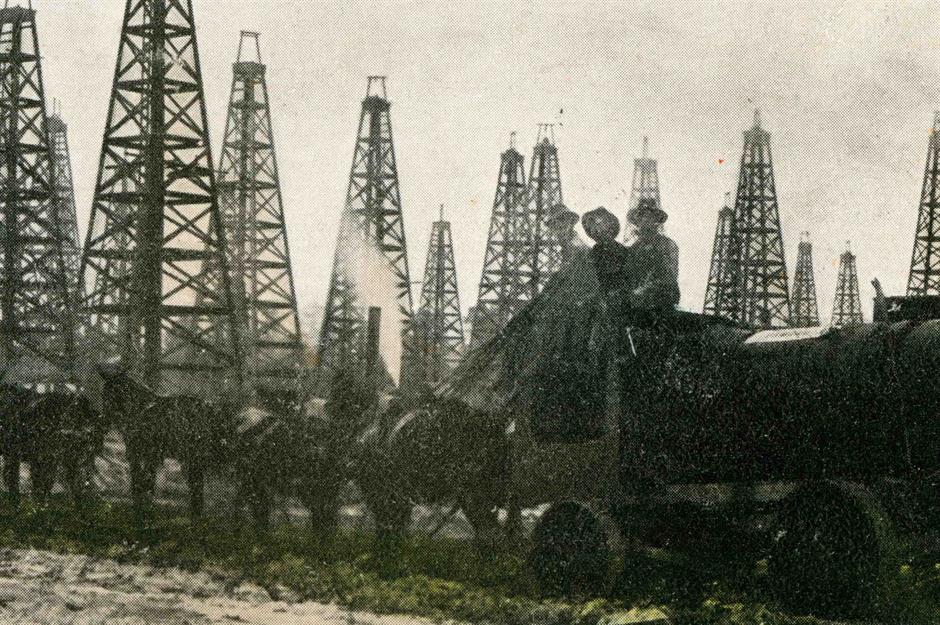

His mother Allene was descended from aristocracy – her ancestors included the man thought to have baptised George Washington, and she was also distantly related to aviation pioneers the Wright Brothers. Meanwhile, his father, Howard Sr., was a buccaneering entrepreneur trying to get rich in the Texas oil boom. In 1909 he struck gold, patenting a new kind of drilling bit that enabled oil wells to pierce granite.

Cleverly, he chose not to sell his revolutionary product but to lease it through his own business. The royalties flooded into his newly created Hughes Tool Company and he soon amassed a fortune.

Early life

Hughes attended exclusive private schools but found it hard to fit in. He was shy and retiring, with no siblings to support him, and had an inherited condition called otosclerosis which made him partially deaf.

His mother was terrified that worse might befall her only child, checking him every day for signs of Polio, which was endemic at the time. She was highly averse to all germs and made Hughes scrub himself with antiseptic, likely planting the seeds of the phobias and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) that would later devastate him.

Early life

A precocious and enterprising child, Hughes had a particular talent for mathematics and technology. He took his first photograph on a Box Brownie camera when he was just three years old. Later, he built a radio receiver from scratch and turned his bicycle into a motorbike with the help of a car starter motor, charging envious local children a nickel a ride.

When his father offered him anything he wished, the 14-year-old Hughes chose a 10-minute aeroplane ride. He found it both thrilling and liberating – an escape, perhaps, from the threatening world below. Flying, photography, enterprise and phobias: the pattern for his life was set.

Hughes (top centre) is pictured here at Fessenden School in Massachusetts, which he reportedly attended in 1921.

Inheritance

The following year, tragedy befell Hughes when his doting, germ-obsessed mother suddenly died. He returned to Texas and enrolled at Rice University to be with his father. But within two years, Hughes Sr. succumbed to a massive heart attack and died too. He bequeathed 75% of the booming Hughes Tool Company to his son, with the rest going to other relatives.

Hughes was just 18 years old but knew exactly what he wanted to do. He abandoned his studies and decided that his future lay in two of his passions: films and flying.

First marriage

Fearing that people in Hollywood would take advantage of him, an aunt persuaded Hughes to marry a local socialite, Ella Botts Rice (pictured). Their marriage would prove shortlived – more on that later.

In another canny move, Hughes also bought his relatives out of their minority stockholding in the Hughes Tool Company, assuming full control himself. However, with his sights set on more glamorous things, he left someone else to manage its day-to-day business.

Moving to Hollywood

Hughes and his new wife moved to Hollywood in 1926. Flush with cash, he spent lavishly and lived the high life. He was determined to make it as a movie producer, but many people saw him as nothing more than a rich-kid dilettante.

When the actor and director Ralph Graves approached him to fund his comedy Swell Hogan, Hughes poured in money, eventually spending twice the $40,000 budget (the equivalent of $712k/£550k in today’s money). The film turned out to be an embarrassing disaster, and he reportedly ordered all the copies to be burnt.

Meanwhile, he found a pilot and made him an offer he couldn’t refuse to give him flying lessons. By 1928, Howard Hughes had his own pilot’s licence, and his movie career was also looking up. His second film, Everybody’s Acting, met with critical acclaim and his third, Two Arabian Knights, was a box office success, even winning an Academy Award for Best Picture.

Perfectionist producer

The film that really made Hughes’ name combined cinema and aviation: an epic drama about World War I fighter pilots called Hell’s Angels.

Production took years. This was partly due to the movie’s groundbreaking aerial scenes, which claimed no fewer than three pilots’ lives. Progress was also hampered by Hughes' perfectionism. He insisted on using real wartime fighter planes, amassing a fleet bigger than many air forces of the day, and he scrapped expensive footage because he thought the cloud formations looked wrong.

After two different directors quit the project, Hughes himself took over directing and even took to the air himself for one shoot. This resulted in his first plane crash, which caused further production delays while he recovered.

The big break

By the time Hell’s Angels was complete, talkies had replaced silent movies. Far from being disheartened, Hughes decided to reshoot parts of it to add sound. This meant finding a new female lead because his first had a thick Norwegian accent which was inappropriate for the part. He cast a then–unknown Jean Harlow in the role, propelling her to stardom.

The movie opened in spectacular style at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard in May 1930. A formation of 50 planes flew over the crowds who gathered to see it, and model planes decorated the street. Hughes’ airborne sequences transfixed the audience, and they gave both him and the film a standing ovation at the end.

In total, Hughes spent a record-breaking $3.8 million (equivalent to $71.8m/£55.3m in today’s money) on Hell’s Angels. The staggering sum arguably paid off, as the picture became the biggest hit of 1930.

Leading ladies

At last, Hughes was now a recognised character in Tinseltown. But he had gained another reputation too: as something of a playboy. In fact, he became romantically attached to dozens of glamourous women over the years, including Katharine Hepburn, Ava Gardner, Ginger Rogers (pictured), Bette Davis and many more.

By 1929, after four ill-fated years of marriage, Ella Rice had filed for divorce. In a happier turn of events, she went on to marry a man named James Overton Winston; the couple stayed married until her death at the age of 87 in 1992.

Hughes' romantic future looked very different. Due to his obsessive and sometimes manipulative nature, the relationships that he formed were often short-lived. There were frequent marriage proposals and some longer-term on-off affairs, but he remained unmarried for nearly three decades after his divorce.

'The Outlaw'

To the consternation of censors, Hughes' lascivious tendencies extended to the silver screen, and he pioneered using racy imagery to promote his movies. For instance, he cast Jane Russell in The Outlaw (pictured), a drama based on the life of Billy the Kid, and proposed dressing her in an outrageous costume he’d designed to accentuate her figure using, as he put it, engineering principles.

The Outlaw was panned by critics, but Hughes exploited Russell’s appeal to turn it into a hit.

The sky's the limit

In 1932 Howard Hughes founded the Hughes Aircraft Company as a division of the Hughes Tool Company. He’d set his sights on the world airspeed record and began designing a special aircraft for the task: The H-1 Racer, which had innovative features such as retractable landing gear and rivets smoothed flush with the airframe to reduce drag.

When the time came to test it, Hughes risked his life by taking to the cockpit himself. Then on 13 September 1935 he flew the H-1 at 352mph (567km/h) over Santa Ana, California smashing the previous record of 314mph (505km/h). Sixteen months later, he piloted an adapted version of the plane from Los Angeles to New York in a little under 7 and a half hours, setting a new transcontinental speed record.

The best was yet to come though. In 1938, Hughes and a crew of four flew around the world in an unprecedented 91 hours, cutting four days off the old record. He said his objective was to demonstrate the viability of long-distance aviation. Returning to the US a national hero, he went on to win awards for his escapades, including the Special Congressional Gold Medal.

TWA

The airline, later known as Trans World Airlines, began life as Transcontinental & Western Air, and its growth to become a household name was in no small part thanks to Howard Hughes. He took control of it in 1939, spending nearly $7 million ($159m/£122m in today’s money) on a majority shareholding, and then applied his customary innovation.

Federal law prevented him buying TWA aircraft from the Hughes Aircraft Company so he approached Lockheed, the builders of the plane he had flown around the world. A secret design project followed and it led to the pioneering Constellation (pictured), a fast, high-altitude airliner that was the first ever to employ a pressurised cabin. This hugely reduced flight times, with significant results...

Billion-dollar profit

By 1950, TWA was expanding its operations globally and changed its name to suit. It acquired a reputation for glamour, flying celebrities and pioneering the introduction of inflight movies, no doubt to Hughes' delight.

A decade later, court proceedings forced Hughes to give up his TWA shares because of a possible conflict of interest with the Hughes Aircraft Company. There were also some concerns within TWA over his erratic behaviour. He fought the move and although he lost, he perhaps had the last laugh; Hughes made over half a billion dollars in profit by selling the stock, the equivalent of around $5.3 billion (£4bn) in today’s money.

Wartime

The United States entered World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, and Hughes was keen to play his part in the national struggle. He put the Hughes Aircraft Company on a wartime footing and secured government contracts to design and construct military aircraft, the biggest of which was his H-4 Hercules seaplane.

Intended to transport troops across the Atlantic and avoid German U-boats, this massive aircraft still has the largest wing span of any ever made, with no fewer than 8 engines and a capacity of up to 750 passengers. To save aluminium, it was constructed of wood. Critics nicknamed it the Spruce Goose, though the actual timber used was birch.

As usual, Hughes micromanaged the project. Often, he would visit the factory by night, ordering alterations for the next day. By all accounts, his suggestions were often excellent, but they contributed to lengthy production delays. In the end, the war was over before the H-4 was ready, rendering it obsolete.

The Spruce Goose

In fact, despite receiving millions of taxpayer dollars, only three Hughes Aircraft Company models ever saw active service. A Senate inquiry later took Hughes to task over this, though it wound up before making its final report.

Hughes was furious at the suggestion of mismanagement and refused to give up on the so-called Spruce Goose. Only one was ever made, and it flew just once. Its one and only journey was about a mile long and piloted, of course, by Hughes. He kept it in an air-conditioned hangar for the rest of his life. You can still see it today at the Evergreen Aviation Museum in McMinnville, Oregon. (The plane is pictured here, complete with a life-sized model of Hughes himself in the cockpit).

And Hughes' love of planes had increasingly disastrous consequences...

Crashing to Earth

Over his lifetime Hughes suffered no fewer than four aircraft crashes. By far the worst of these occurred on 7 July 1946 when he was flying an experimental US Army spy plane over Los Angeles. It had two propellers per engine, each turning in a different direction. An oil leak caused one of these to malfunction and he lost control of the aircraft, smashing into houses in Beverley Hills.

The plane burst into flames and it was only by luck that Hughes survived. He was rescued from the wreckage and his injuries included a collapsed lung, crushed collar bone, cracked ribs and 75% burns. These affected him for life; in severe pain, he needed to take morphine and later codeine, which he became addicted to.

Some biographers have suggested that air crashes might even have left Hughes with brain damage, and that this could account for the bizarre behaviour he exhibited in later life.

RKO

Meanwhile, Hughes certainly hadn't abandoned his love of film. Between 1948 and 1955, he saved major Hollywood studio RKO – which was one of the ‘Big Five’ studios in the 1930s but had fallen on hard times by the 1940s – by buying up some $24 million ($282m/£218m today) of shares, effectively making him its sole owner.

RKO was particularly concerned about communist infiltration. The Cold War was underway and the US had become hyper-vigilant about Soviet sympathisers. Accordingly, the first thing Hughes did was to fire much of the workforce and shut down productions while he rooted out alleged Reds.

Middle age

Many releases followed, though, often featuring Jane Russell or whichever girlfriend he had in tow at the time. On set, Hughes reportedly switched between being an extreme micromanager and showing a relative lack of interest. He was by now middle-aged and developing a taste for younger and younger women.

He would invite those who caught his eye to audition, then house them under the close observation of his aides who bugged their apartments and tapped their phones. Promised movie parts often never came. Some complained; some succumbed to his charms.

In 1955, Hughes sold RKO and moved on from Hollywood, declaring it “too complicated” for him. He reportedly walked away from some $6.5 million ($76.5m/£59m today) in profit.

Reaching for the stars

Although Hughes suffered some controversy over his government projects during World War II, they continued to be a huge money spinner for him in the post-war years. He realised that his companies’ future lay in the growing field of military electronics rather than just making airframes, and so with the help of some of the age’s most talented young scientists he set about this.

In 1947 he founded Hughes Helicopters. Then in 1948 he began another new operation called the Hughes Aerospace Group. Yet more companies followed, becoming major US defence contractors as the Cold War progressed. They went on to develop ballistics including the US Air Force’s first guided air-to-air missile, air traffic control systems, and dazzling space-age technology such as Surveyor 1, the first craft to land on the Moon.

Between them these companies made billions of dollars in profit, and their successors still do. (The Hughes Space and Communications Company, for example, was purchased by Boeing in 2000).

Giving it all away

Hughes disliked tax. One reason for his decision in later life to live in a series of hotel rooms was to be officially resident at no single address and so avoid state taxes. An extraordinary move he made in 1953 was in keeping with this logic: he founded a charity and donated his entire stock in the Hughes Aircraft Company to it. Naturally, the charity concerned bore his name: The Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI).

This effectively made the Aircraft Company itself a tax-exempt charity. The US government fought the decision but ultimately lost. As so often with Hughes though, it’s hard to determine all the motives for his cost-cutting – as well as being a shrewd businessman, he was also undoubtedly a genuine philanthropist.

He founded the Medical Institute with the express objective of understanding, as he put it, "the genesis of life itself". One president of the HHMI has speculated that Hughes might have alighted on the cause in his teens after his parents’ sudden deaths.

The richest man in the US

On 12 January 1957 Hughes married again, this time to an actress he’d known for many years called Jean Peters (pictured). According to some accounts she was the only woman he ever loved; others claimed he only married her to avoid being sectioned.

At any rate, the marriage seems to have been troubled and Hughes became ever more reclusive. The media said the couple rarely met in person, speaking only by phone. As the years went on there were reports that Hughes was mentally unstable, terminally ill, or even already dead.

In 1958 he suffered a nervous breakdown. He was immensely rich and successful in business – by the 1960s he had reached billionaire status, an incredible achievement for the time, and was the richest person in the whole US – yet increasingly found the world around him hard to bear.

High roller

Hughes had been buying up vast tracts of land in the Mojave Desert outside Las Vegas for years, even becoming Nevada’s largest landowner. Finally, despairing of Californian taxes, he left to live in the Silver State.

Some of Hughes’ most famous eccentricities stem from his time in Nevada. He moved into the Desert Inn in Las Vegas in November 1966. The story goes that the hotel needed him to vacate his room on New Year’s Eve because another guest had booked it. Hughes simply bought the hotel for over $13 million ($127m/£97m in today’s money) – and stayed. Then he bought the casino opposite because its neon lights disturbed him.

In fact, over two years Hughes spent the modern equivalent of around $2.7 billion (£2bn) buying numerous Vegas hotels and casinos, becoming Nevada’s largest employer as well as the state's largest landowner. He bought the local TV station too, and reportedly ordered them to replay movies from the start if he missed part of one. On one occasion, he watched movies for months on end, barely eating or sleeping. For the next four years, he did not leave the Desert Inn.

Las Vegas legacy

For all Hughes' reclusiveness, his impact on Las Vegas was profound – and positive. The city had previously been a money laundering centre for the Chicago mob, but as Hughes bought up the town, the Mafia’s influence declined, and its gambling economy became more appealing to legitimate investors. Hughes continued business through his own so-called Mormon Mafia – a small group of aides whom he believed were more trustworthy because of their religion’s ban on smoking and drinking.

But as the city he lived in flourished, Hughes himself was undergoing a dramatic decline. Over his last two decades, Hughes succumbed to the conditions that he’d endured for years. He was in enormous pain from his plane crash injuries and addicted to codeine. His deafness increased. Most of all, his OCD seems to have taken control of him...

Illness and paranoia

Hughes retreated, shutting out the world with heavy curtains and blacked-out windows. His diet was poor and his germphobia spiralled out of control, compelling him to wash his hands until they bled and burn his clothes if he thought they weren’t clean enough. As depicted in the 1977 biopic, The Amazing Howard Hughes starring Tommy Lee Jones (pictured), he rarely shaved or cut his hair, fingernails and toenails. He spent the last few years of his life in hotel rooms in the Bahamas, Britain, Canada and Nicaragua, ending up in Mexico. In 1971, Jean Peters divorced him after 14 years of marriage.

Some people have argued that Hughes may have caught syphilis during his wild Hollywood years and that the illness had started to attack his brain. Whether or not this is true, his life undoubtedly became both bizarre and squalid. As he was so wealthy and powerful, his aides found it hard to challenge his behaviour.

By the early 1970s, there was huge public interest in Hughes’ life and the mystery surrounding him. It was the perfect time for a hoaxer to get rich by writing what was purported to be his autobiography...

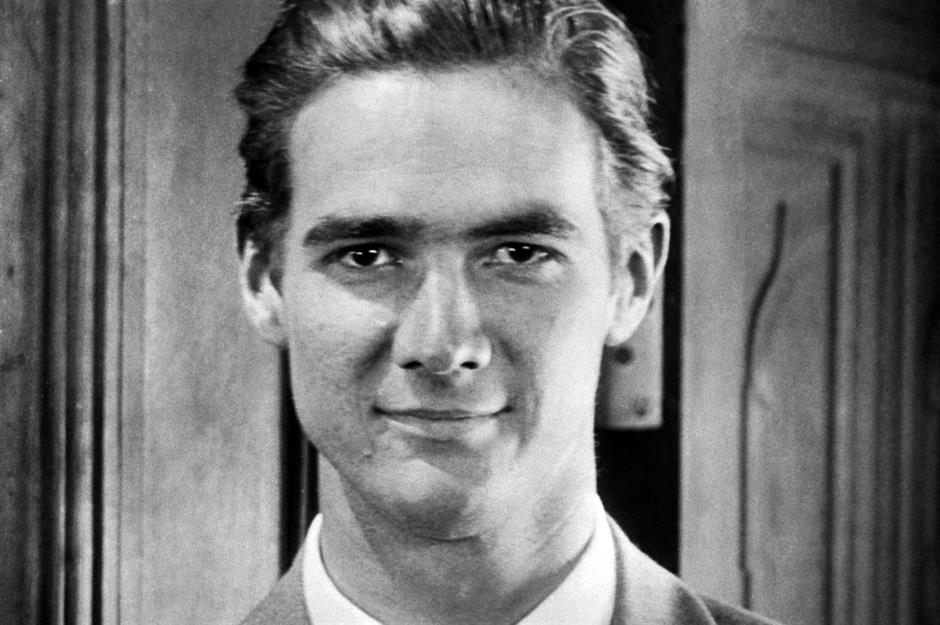

The memoir controversy

Clifford Irving (pictured) was a writer based in Ibiza and, as the son of a cartoonist, he was able to mimic people’s handwriting. He researched anecdotes he could cite to suggest he'd met Hughes, then passed off forged letters as evidence that Hughes had commissioned him to write an authorised memoir. Incredibly, he managed to deceive both Life magazine and a publisher, McGraw-Hill, which paid him a $750,000 advance – the equivalent of $5.8 million (£4.5m) today.

Irving reasoned that because Hughes was so reclusive, he would not challenge his audacious scheme. However, in January 1972 the billionaire shocked the world by holding a telephone press conference from his Bahamas hotel room, denouncing the book as a sham. There was never a film script so wild as Irving’s account, he said.

Clifford Irving later stood trial for fraud and served 17 months in prison. But later in life he became a minor celebrity over the incident, which was also recalled in a 2007 film called The Hoax, starring Richard Gere.

Death in the sky

It was perhaps fitting that the man who did so much to advance aviation should die in the air. On 5 April 1976, Howard Hughes was en route from Acapulco, Mexico to the Methodist Hospital in Houston for urgent medical treatment when he breathed his last. A doctor travelling with him in a private jet said that he died at 1.27pm while they were flying over southern Texas.

Hughes was taken to the hospital where his body was watched over by armed guards. Lurid reports emerged about its condition. They said Hughes was virtually unrecognisable, as emaciated as a Japanese prisoner-of-war, with his hair, fingernails and toenails grown grotesquely long. The FBI had to use fingerprints to identify him.

An autopsy subsequently recorded the cause of death as kidney failure. It found substantial quantities of codeine and diazepam in his system. X-rays found broken-off hypodermic needles in his skin. For all his vast wealth, Howard Hughes had suffered years of neglect at his own hands. He is buried at the Glenwood Cemetery in Houston – but as his body was laid to rest, rumours about his will jumped into life...

The disputed will

Hughes’ net worth at the time of his death was around $2.5 billion – approximately $13.9 billion (£10.7bn) in today’s money. Surprisingly for someone with such enormous wealth, he died intestate and it wasn’t long before third parties came forward to try their luck claiming a share of his riches – some 600 of them, in fact.

These included Melvin Dummar, a delivery driver who said that in 1967 he’d encountered a dishevelled old man on a Nevada desert highway and given him a free ride to Las Vegas. The man had apparently revealed himself to be Howard Hughes. Dummar presented a handwritten will which he claimed was delivered to the Mormon Church of the Latter-Day Saints in Salt Lake City. The will said Hughes had left him one-sixteenth of the estate – approximately $156 million ($864m/£666m today).

A seven-month trial found inconsistencies in the so-called Mormon Will, and in 1978 it was deemed to be a forgery. Dummar received nothing though he escaped any fraud charges. He's pictured here in 2005 after signing copies of The Investigation, a book written about the case.

The disputed will

Another claimant was one of Hughes’ ex-girlfriends, the actress Terry Moore (pictured alongside a poster of Hughes). Moore said they had secretly married in 1949 aboard a yacht in international waters off the coast of Mexico, and that the union was never annulled. She could not provide any proof of this, however in 1974 Hughes’ estate paid her an undisclosed sum in return for dropping her case. Moore went on to write a best-selling book about the affair, Beauty and the Billionaire.

Hughes' riches eventually went to his cousins but it was 2010 before they got their final instalment, when a bankrupt shopping mall owner paid out for the estate’s last outstanding property asset.

Before he died, Hughes increasingly focused on real estate and his heirs continued this trend. They developed a district west of Las Vegas called Summerlin, named after Hughes’ grandmother. Summerlin is a planned community built around golf courses, greens and artificial lakes. It’s home to some notable residents and also the appropriately named minor league baseball team, the Las Vegas Aviators. It stands as testimony to the man who yearned for tranquillity, seclusion – and low taxes.

Legacy

Hughes' other achievements are still with us too. His contribution to the development of long-haul flying is especially relevant. He also pushed the boundaries of cinema, launching the careers of some of its most famous stars, and helped make Las Vegas what it is today. The companies he founded contributed enormously to American (and Western) security during the Cold War. Perhaps his most enduring legacy, however, is the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the research and scientific education that it continues to sponsor as an independent foundation.

Hughes once said that above all he wanted to be remembered for his role in aviation. But his extraordinary life means that he will also be remembered for much more – not just as a complex and troubled individual but one of the most impressive of the 20th century. More broadly, his life reveals an important lesson: a cautionary tale about the ability of extreme wealth to empower but also entrap.

Now discover the richest person in the world in every decade from 1820 to 2020