World-changing inventions people said wouldn't be popular

Game-changing innovations that were savagely mocked

Fork

Exactly when the fork was invented is open to question, but this essential piece of cutlery is thought to have been introduced to the Western world in the 10th century by Byzantine princess Theophano Skleraina (pictured), the wife of Holy Roman Emperor Otto II. Although some historians credit its arrival in Europe to another Byzantine princess, Maria Argyropoulaina, who married the Doge of Venice's son in 1004.

Fork

Sponsored Content

Printing press

Printing press

Umbrella

Today the umbrella is an essential accessory in rainy England. In fact, the average person in the country owns two of the things. Yet the first man to carry an umbrella in the nation was bombarded with insults, pelted with garbage and almost run over and killed by a coach. Jonas Hanway shocked fellow Londoners in the 1750s when he took to using an umbrella in the city's streets.

Sponsored Content

Umbrella

An import from Persia via France, the accessory was considered taboo for men to carry and thought of as a sign of a weak, effeminate character. Hanway also drew the ire of coach drivers (behind two-wheeled, horse-drawn carriages) who feared the accessory would steal away their business, which flourished on wet days. Stubborn, Hanway ignored the haters even when one coach driver went as far as trying to run him over. Within decades the stigma attached to umbrellas vanished and they have come to be ubiquitous across the world.

Vaccines

In 1796 English country doctor Edward Jenner pulled off a sensational medical breakthrough when he inoculated an eight-year-old boy with cowpox to protect against the far more deadly smallpox after noticing milkmaids, who were routinely exposed to the more benign bovine pathogen, seemed immune to the devastating human disease. The experiment was an unmitigated success. Jenner coined the term vaccine from the Latin word 'vacca', meaning cow, and published his findings in 1798.

Vaccines

Instead of being lauded for his discovery, Jenner was lampooned, particularly by religious leaders, who were horrified the physician was going against the will of God and using pus from diseased animals to inoculate people. The press also poured scorn on Jenner, as you can see from this satirical cartoon by James Gillray, which shows vaccinated individuals growing grotesque cow's heads. Thankfully the disdain for Jenner's discovery dissipated and vaccination eventually become commonplace.

Sponsored Content

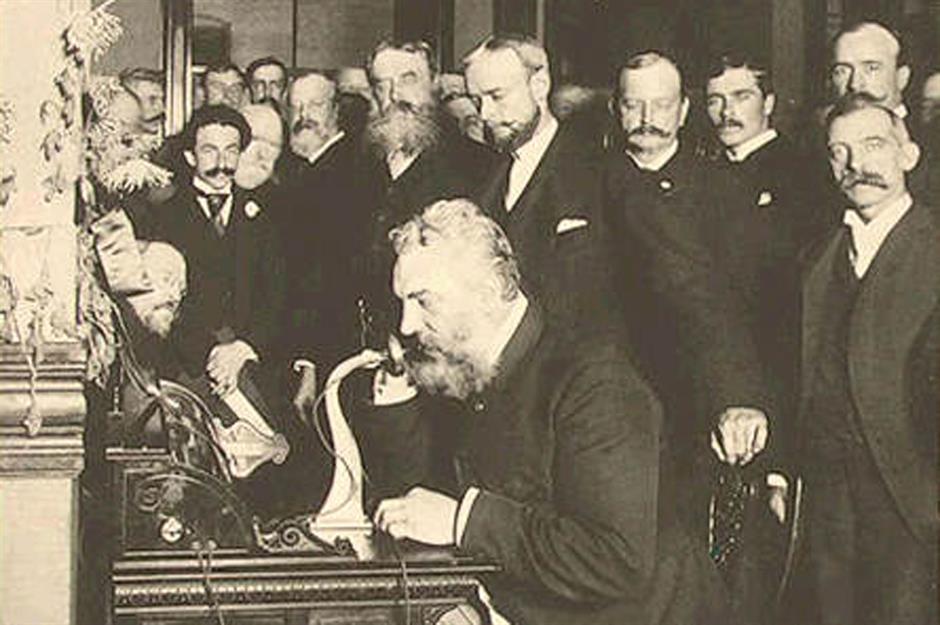

Telephone

Father of the telephone Alexander Graham Bell was awarded the first patent for the device in 1876 and is credited with creating the first practical incarnation of the trailblazing technology. Few saw its tremendous potential however. After Bell tried to sell his telecoms business to Western Union, its president William Orton exclaimed “What use could this company make of an electrical toy?”

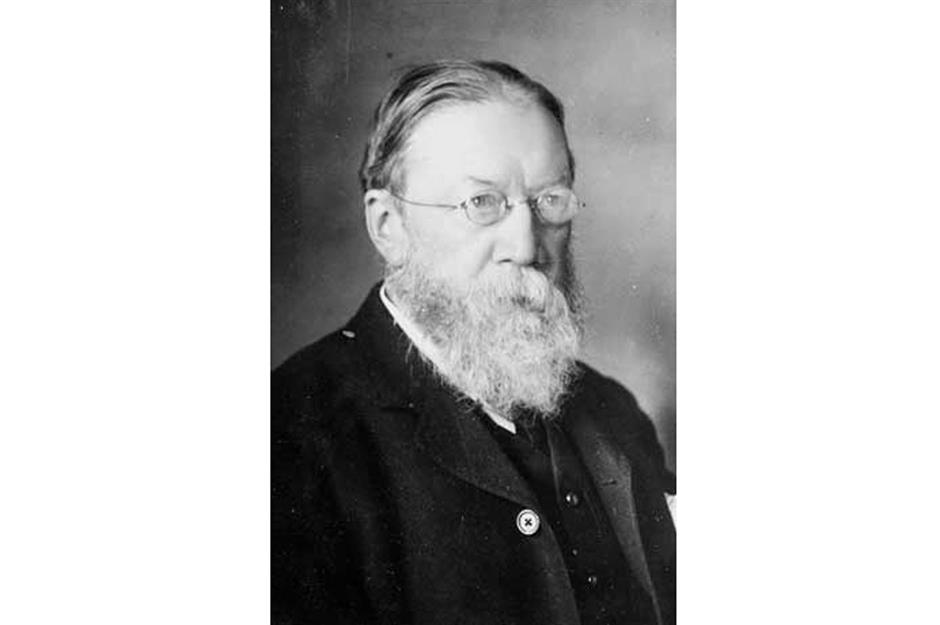

Telephone

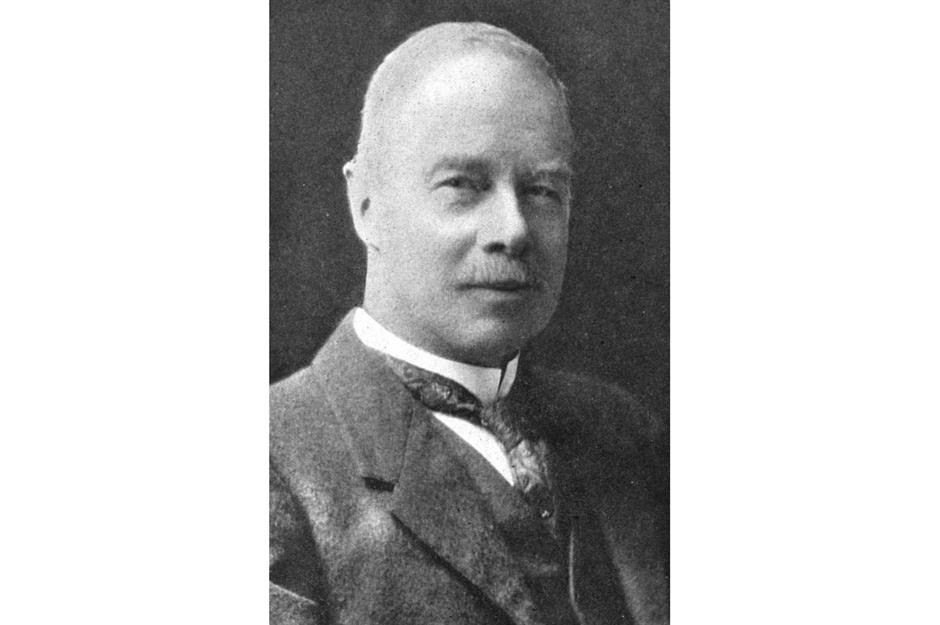

People even thought an American mayor was being overly optimistic about the future of the telephone when he predicted that “one day, there will be one in every city”. The reception was similarly cool in the UK. Sir William Preece, the chief engineer of the British Post Office (pictured), was convinced the technology would never go mainstream in England. “The Americans have need of the telephone, but we do not. We have plenty of messenger boys”, he is quoted as saying.

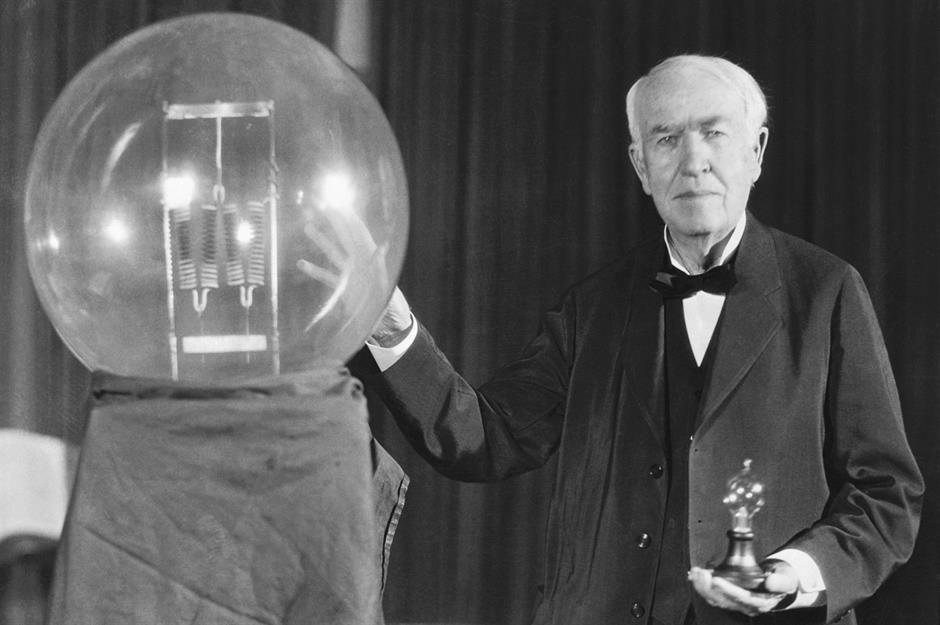

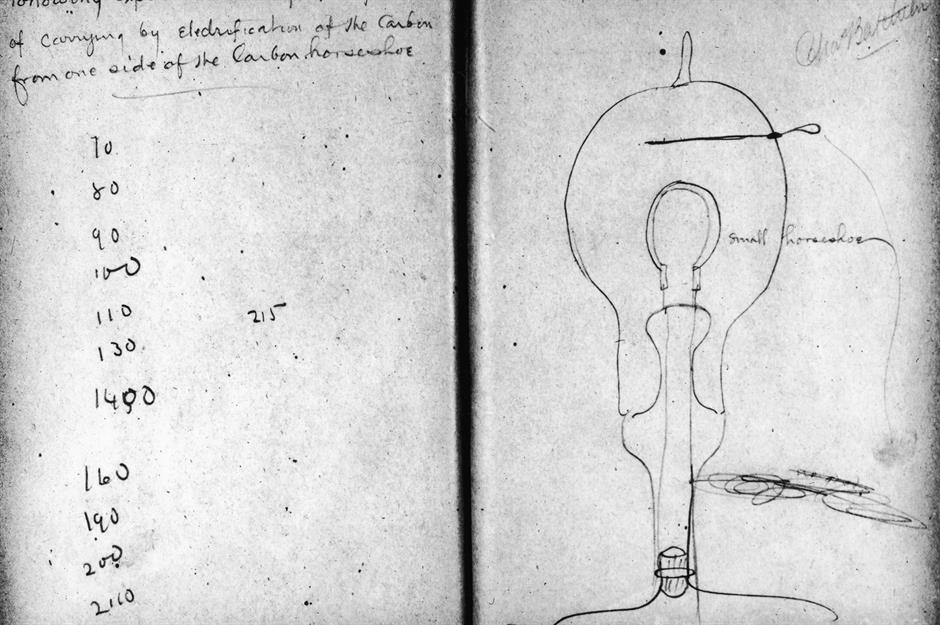

Electric light bulb

Thomas Edison patented the world's first commercially-viable electric light bulb in 1879. Despite its ingenuity, the technology had more than its fair share of influential critics, most notably Professor Henry Morton of the Stevens Institute of Technology. He slammed the invention, calling it a conspicuous failure trumpeted as a wonderful success.

Sponsored Content

Electric light bulb

As was the case with the telephone, experts in the UK were even more contemptuous of Edison's innovation. A British parliamentary committee snootily concluded that the American invention was “good enough for our transatlantic friends... but unworthy of the attention of practical or scientific men”, while Sir William Preece, who was clearly no stranger to bad predictions, called it an “absolute ignis fatuus ['foolish fire']” – basically a will-o'-the-wisp or false hope.

Now read about accidental inventions that made a fortune

Daylight saving time (DST)

Daylight saving time (DST)

Indeed the very notion of playing around with time was thought of as preposterous. One member complained that it was “out of the question to think of altering a system that had been in use for thousands of years”, while another criticized the concept as unscientific and impractical. Hudson had the last laugh of course when DST was adopted in Ontario, Canada in 1908, with countries around the world soon following suit.

Sponsored Content

Bicycle

Bicycle

Female cyclists in particular were the objects of ridicule, as you can see from this Punch magazine cartoon from 1898, and journalists were quick to dismiss the bicycle as a silly short-lived craze. In 1902 The Washington Post declared the activity a passing fancy, while the New York Sun confidently proclaimed the death of the pastime in 1906.

Automobile

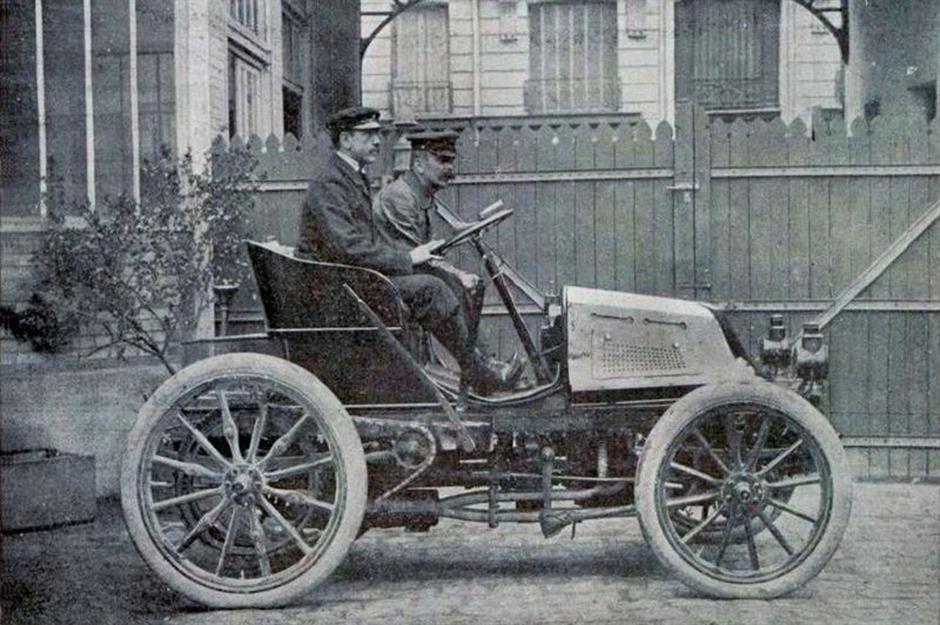

Cynics rushed to disparage the automobile too. Literary Digest weighed in on the technology in 1899, concluding that “the ordinary 'horseless carriage' is at present a luxury for the wealthy; and although its price will probably fall in the future, it will never, of course, come into as common use as the bicycle”.

Sponsored Content

Automobile

The New York Times agreed, stating in 1902 that the price of automobiles “will never be sufficiently low to make them as widely popular as were bicycles,” while the following year the President of the Michigan Savings Bank warned Henry Ford's lawyer Horace Rackham not to invest in the Ford Motor Company on the grounds that “the horse is here to stay, but the automobile is only a novelty – a fad”. Ford didn't take any notice of this warning and his investment in the mass production of cars was a key driver behind the great future success of cars.

Discover the tech and inventions that show why China is the best in the world

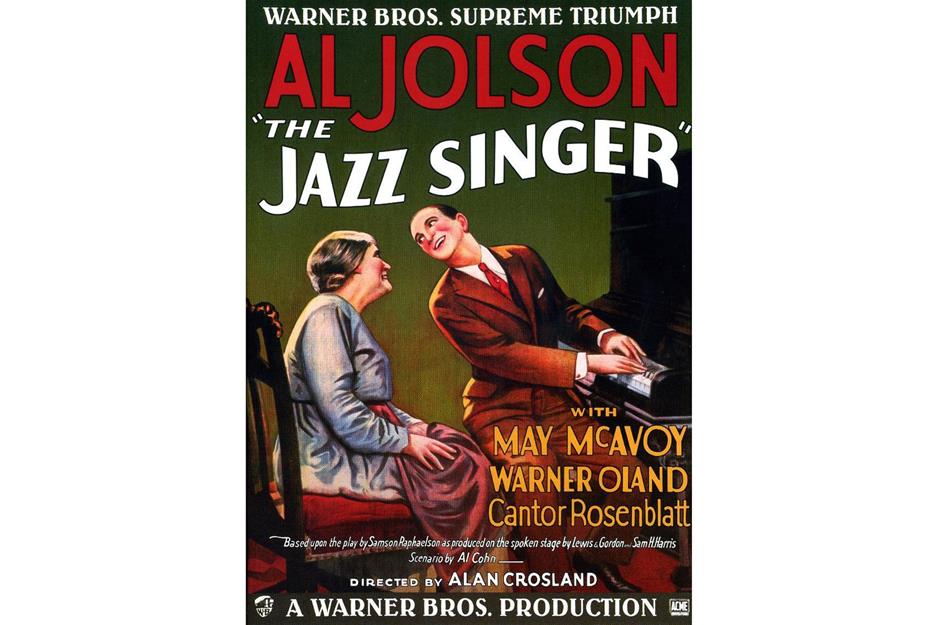

Sound film

The first 'talkies' were actually produced by pioneering French director Alice Guy-Blaché in the early 1900s. But movies incorporating synchronized dialogue didn't take off until 1927 with the release of Hollywood blockbuster The Jazz Singer, which spelled the end of the silent movie era. That said, despite the film's huge success, early sound movies had plenty of powerful detractors.

Sound film

United Artists president Joseph Schenck surmised in 1928 that “talking doesn't belong in pictures”, while across the pond British film studio boss John Maxwell dismissed the talkie as “a costly fad”. Hollywood stars were equally disdainful of the new technology. Actress Mary Astor wrote in the 1960s that many artists of the era considered The Jazz Singer a box office gimmick and reckoned that sound movies would “drive audiences from the theaters”.

Sponsored Content

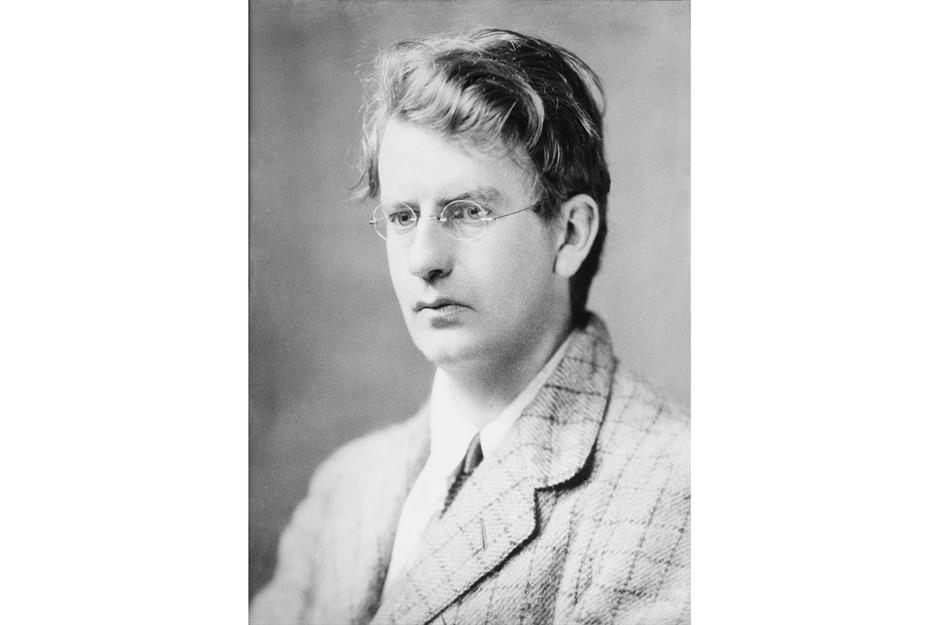

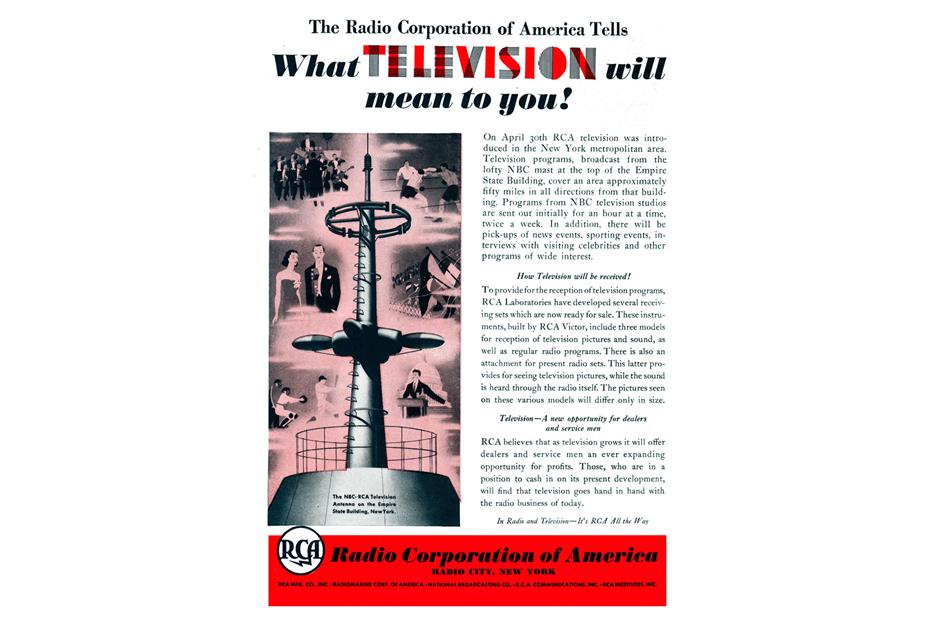

Television

Scottish inventor John Logie Baird introduced the TV to the world in 1926, attracting sceptics from the start. When Baird turned up at UK newspaper the Daily Express' offices to showcase his creation, the newspaper's editor ordered a staff member to “go down to reception and get rid of the lunatic... He says he's got a machine for seeing by wireless. Watch him – he may have a razor on him". That same year radio pioneer Lee DeForest judged TV to be “commercially and financially... an impossibility”.

Television

In 1939 the New York Times stressed that "TV will never be a serious competitor for radio because people must sit and keep their eyes glued on a screen; the average American family hasn't time for it.” Meanwhile, 20th Century Fox boss Darryl Zanuck claimed in 1946 that “TV won't be able to hold on to any market it captures after the first six months. People will soon get tired of staring at a plywood box every night." And in 1948 BBC radio exec Mary Somerville called the technology “a flash in the pan".

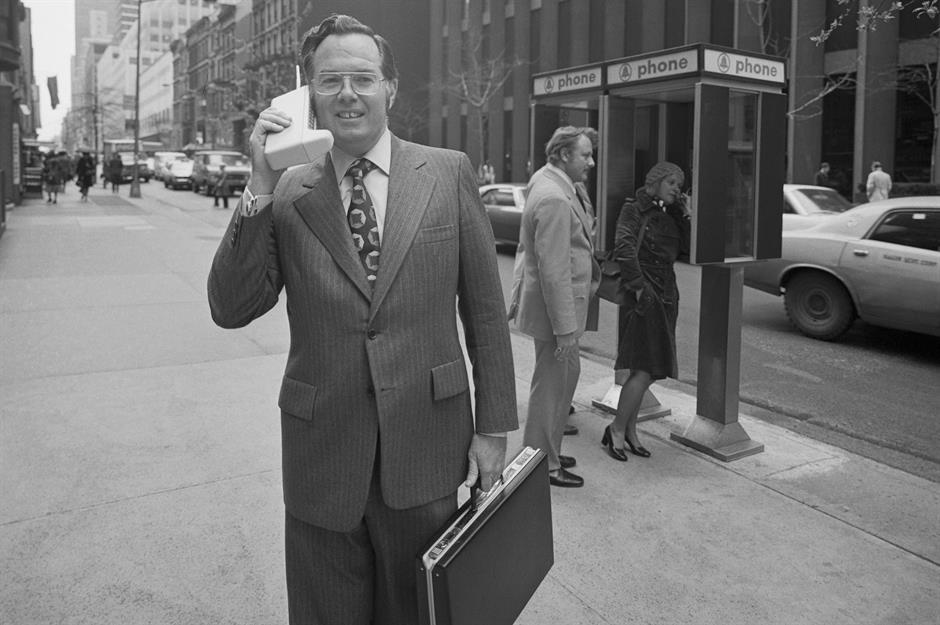

Cellphone

Back in the early 1980s mobile/cellular phones were heavy brick-like devices, expensive to purchase and use and the sole preserve of rich business people. No wonder the future of the technology appeared bleak to some experts. A 1980 report by McKinsey for AT&T predicted that the mobile phone would be a strictly niche device with just 900,000 users in the US by 2000. In reality the total number of users that year hit 108 million.

Sponsored Content

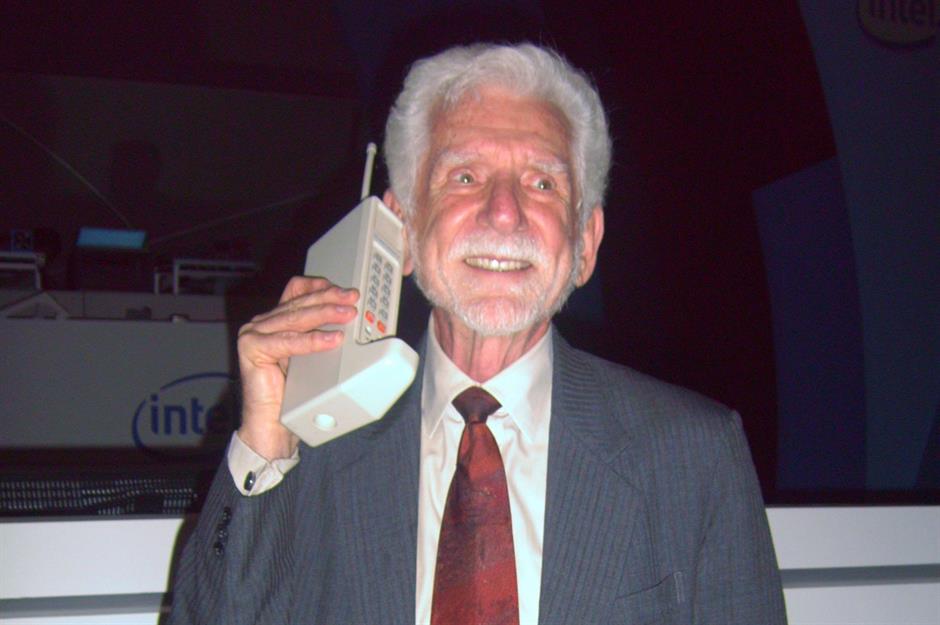

Cellphone

In 1981 telecoms consultant Jan David Jubon was unconvinced the technology had any future: “But who, today, will say I'm going to ditch the wires in my house and carry the phone around?” And Marty Cooper (pictured), the engineer that led the team that built the first cellphone, was himself pretty lukewarm about the technology, saying: “Cellular phones will absolutely not replace local wire systems. Even if you project it beyond our lifetimes, it won't be cheap enough."

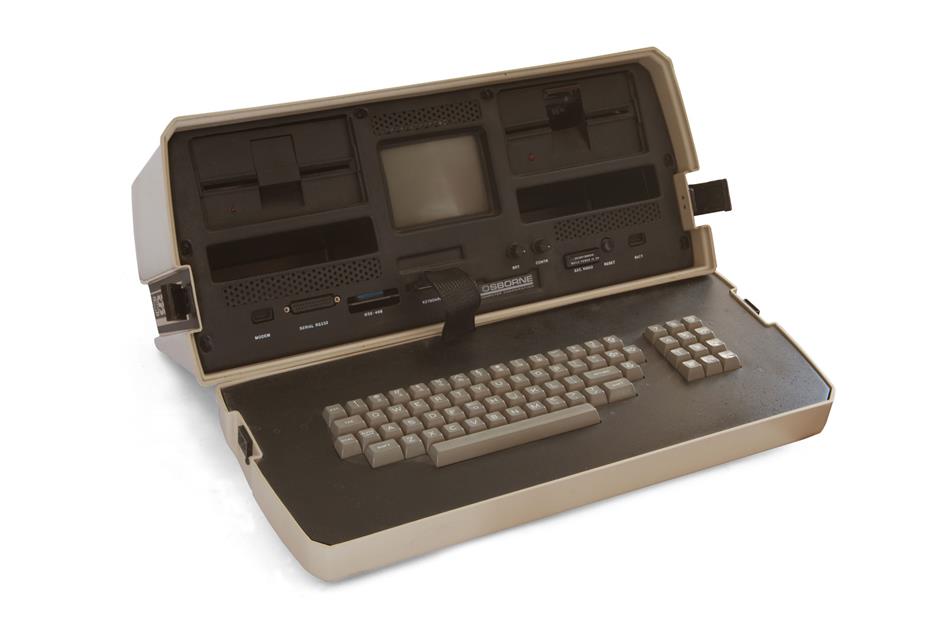

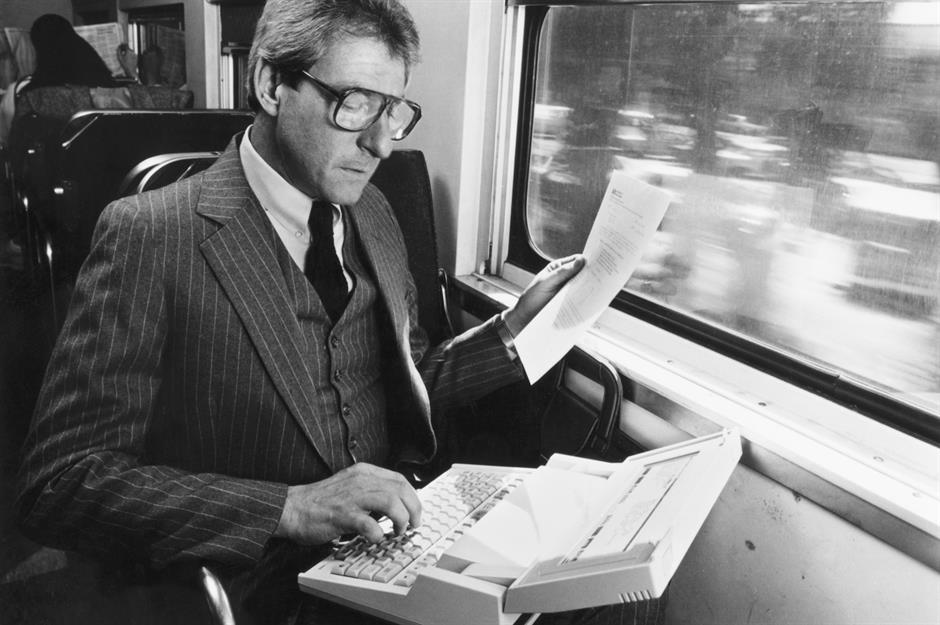

Laptop

Laptop

Given these drawbacks it comes as no surprise that some experts dismissed the laptop as a fad. For instance New York Times tech writer Erik Sandberg-Diment penned an article in 1985 deriding the innovation and predicting its sad demise. The journalist believed the average user would never want to lug around a laptop and compute on the move, and thought the gizmo had little chance of catching on widely.

Sponsored Content

Even during the mid-1990s when email was going mainstream naysayers were dismissive of the technology. In 1994 UK government officials mulling over whether to set up an email account for the then-prime minister John Major claimed that the new method of exchanging messages would likely never catch on.

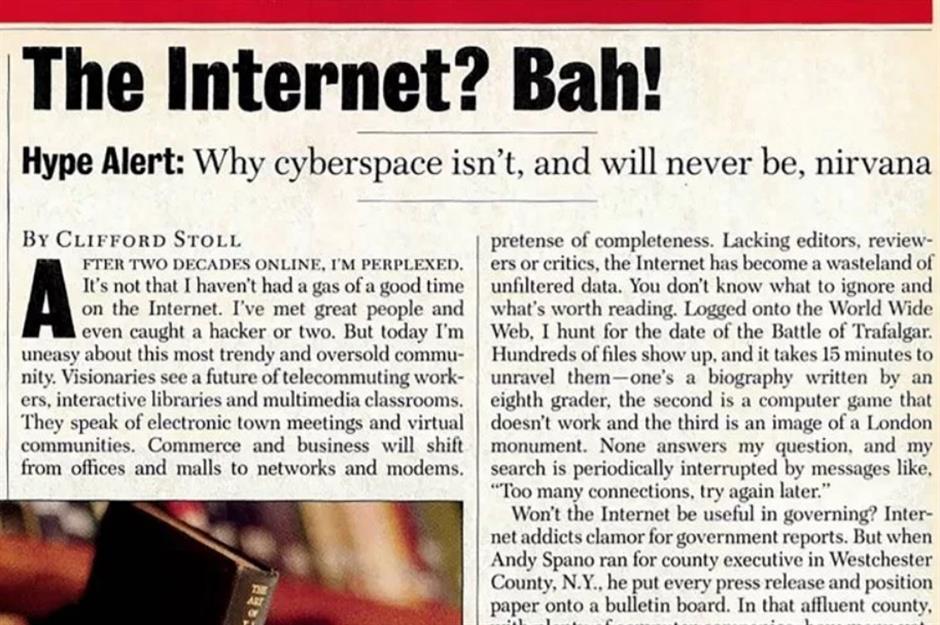

Internet

Back in the mid-1990s a number of experts were less than keen on the internet, which they viewed as a nerdy fad that would end up going nowhere. By way of example, a now-infamous article penned by scientist Clifford Stoll in 1995 for Newsweek entitled 'The Internet? Bah!' slammed the innovation and predicted it would crash and burn.

Sponsored Content

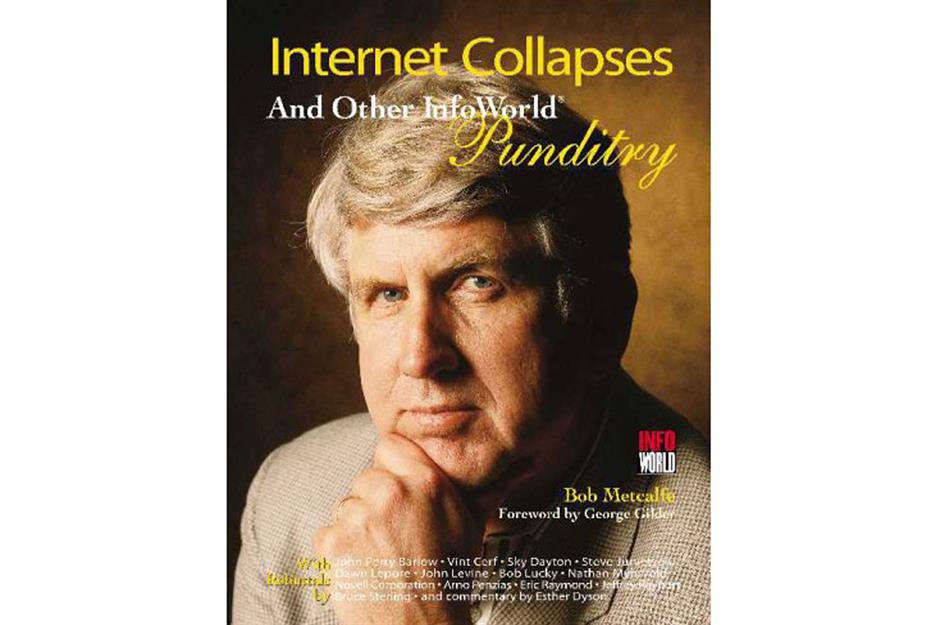

Internet

Also in 1995, Ethernet inventor Bob Metcalfe (pictured) wrote in an opinion piece for InfoWorld magazine that “the internet will soon go spectacularly supernova and in 1996 catastrophically collapse”. Metcalfe vowed to eat his words if he was wrong, and did just that at the World Wide Web Conference in 1997 when he blended a copy of the article with some water and drank the concoction.

Now read about the famous inventions their creators regretted

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature