The notorious fraudster who sold the Eiffel Tower... twice

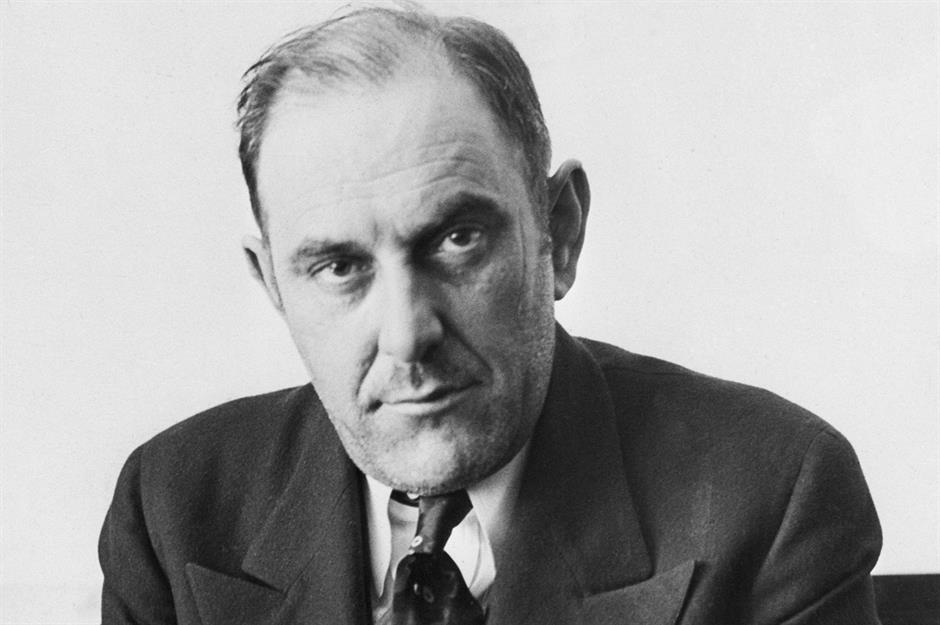

The smoothest con man that ever lived

They called him the smoothest con man that ever lived. Moving seamlessly between high society and the underworld, with matinee idol good looks, perfectly manicured and unfailingly well-mannered, he was responsible for some of history’s greatest scams, tricking the ultra-wealthy on both sides of the Atlantic.

In Depression-era America, he forged banknotes so convincing they almost risked collapsing the economy. In Europe, he sold the Eiffel Tower… twice. Who on Earth could carry off such audacious frauds?

Read on to discover the incredible story of Victor Lustig.

All dollar amounts in US dollars.

The charming cheat

Victor Lustig was outrageous and manipulative in his schemes, yet he charmed many and drew the admiration of many more. He was certainly inventive in his mischief.

Consider this: He was an excellent pool player who might even have made professional had he ever put his mind to it. Instead, he chose to cheat. He’d play a frame or two for a modest bet, but do it left-handed and ensure he narrowly lost. Paying up happily, he’d then suggest another frame, this time with a much larger bet and offering to play only using his right hand as a handicap. He could make a tidy sum in an evening this way.

Over his life he made millions of dollars more from an ever-growing repertoire of deceit. But he was a spender, a gambler and a bon-viveur, so his illicit gains never satisfied him for long, and he always needed another scam. It seems likely that he thoroughly enjoyed fooling people, too.

International mystery man

The charming Victor Lustig had many alter egos and it’s not certain which was the real person. In fact, were any of them the real him? No one knows. He used no fewer than 47 aliases throughout his life and he had dozens of passports in different names.

Fluent in six languages, his favourite guise was that of a European aristocrat whose family owned several beautiful castles. This seems to have made an impression: even the FBI referred to him as 'The Count' and dubbed their project to track him down 'Operation Dracula'.

His nobility was - of course - a complete fake; his real roots may have been quite modest. But 135 years after his birth, we’re no nearer to knowing for sure.

Sponsored Content

Lost childhood

Lustig told police that he was born in a small town called Hostinné (pictured) on 4 January 1890. The town is part of the Czech Republic today. Biographers have found information suggesting that he was indeed from there. But the evidence trail doesn’t go much further.

He also declared that his father had once been Hostinné’s mayor. Later, however, he described his parents as "the poorest of people". It’s unlikely that both these claims can be true, and as there’s no proof that his father was anything more than a minor local government official, the latter is more probable.

Lustig almost certainly embellished his back-story to impress people he met, just as he fabricated so much else. And with his silken multiple personas, few seemed ever to question it.

Early crimes

We do know that as a teenager, Victor Lustig became an experienced petty criminal. He quickly moved from pickpocket to panhandler and then street hustler. Having taken to gambling, he became a card sharp. True-life crime magazines of the time describe him as perfecting every card trick going.

Moving between Vienna, Prague, Paris and London, he applied his quick thinking to an ever-growing range of scams, such as selling fake documents he said once belonged to famous people like the Wright Brothers and Abraham Lincoln. Or pretending to be an insurer and making off with expensive jewellery people asked him to value.

Sharp wits. Sharp tricks. Sharp in other ways too: It was around this time that Lustig received a scar across his cheek from a Paris love rival. Later, he’d pass it off as the result of an aristocratic duel.

Robbing from the rich

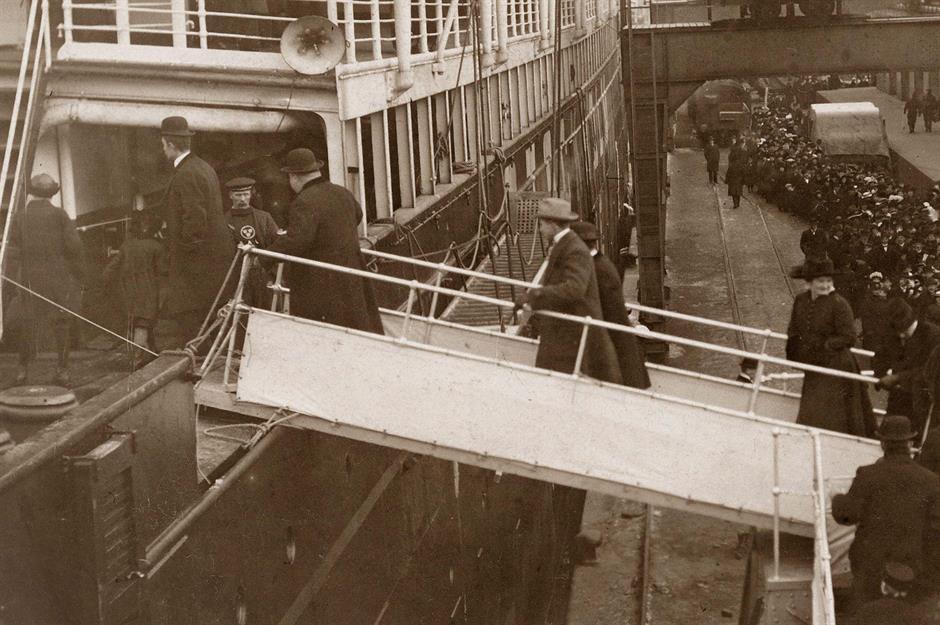

The suave trickster always claimed he only targeted the rich and greedy. He found plenty of them on the transatlantic liners operating between France and New York. He’d confide in them over several days at sea, eyeing them up as potential victims.

He would pose as a big-shot Broadway producer, looking for investment for his next hit show or some other tall story that he was already expert at fabricating. He hooked up with an accomplice too, and together they worked the poker tables, cheating their way to a small fortune.

The ruses usually worked, and the beauty of it was that Lustig and his partner in crime had disembarked and made a clean getaway by the time anyone discovered he was a conman.

Sponsored Content

Coming to America

When war broke out in 1914, the liner trade dried up. Lustig now decided to move to the United States in search of further greedy and gullible targets.

Some of his early American ventures were elaborate; others were distinctly low-tech. At one point he set up a fake church on the Manhattan waterfront, close to where the ocean liners docked. Delivering a copied sermon, he so moved his congregation that they stumped up over $90 (more than $2,500/£1,975 in today's money) in the collection that followed. All of which found its way into the fake priest’s pockets.

At the other end of the scale was his fake horse racing scam. This involved renting premises that he dressed up as an off-track betting shop. He hired actors to play the part of other punters and had impersonators in a room next door to relay bogus race commentaries. The money poured in; Lustig knew that gamblers parted with their cash quicker than most people. Weirdly, their horses never seemed to win…

The money box scam

One of the most elaborate of all Lustig’s tricks was what he called the 'Rumanian Money Box', a device that he claimed could perfectly duplicate one-hundred-dollar bills. It resembled a wooden travel chest with complicated dials and printing machinery inside. He said it worked using radium, and the process took several hours.

Demonstrations impressed those invited to witness it: A piece of white linen paper inserted at one end eventually emerged as a genuine banknote at the other. But that’s because what emerged was a genuine banknote, pre-loaded by Lustig.

After showing the device in action, Lustig would lure his associate into making an offer for it. He would typically feign reluctance at first but eventually agree. Victims frequently paid thousands for it - in one case, more than $40,000. That would be over $600,000 (£470,000) in today's money. The Money Box certainly did make a lot of cash. But only for Victor Lustig. He could build each one in just a few hours.

Speaking easy, scamming hard

After the war, the Roaring Twenties beckoned and Lustig expanded into further scams, such as bogus real estate and commercial deals. He attracted the attention of law enforcers in 40 American cities yet got the better of them and made a fortune.

It was the age of Prohibition, speakeasies and lucrative crime. The police nicknamed Lustig 'The Scarred' after his facial injury. However, unlike many of the other tricksters at the time, he was not a violent man. He never carried a gun and was just 1.7m tall and weighed 63kg. He was also respectful, including to women.

On 3 November 1919, he married and later had children. His daughter, born in 1922, remembered him as a devoted father who lavished the proceeds of his crime upon his family. Ever deceitful, he also took on many lovers including a brothel keeper named Billy Mae Scheible and spent thousands on a gambling habit.

Sponsored Content

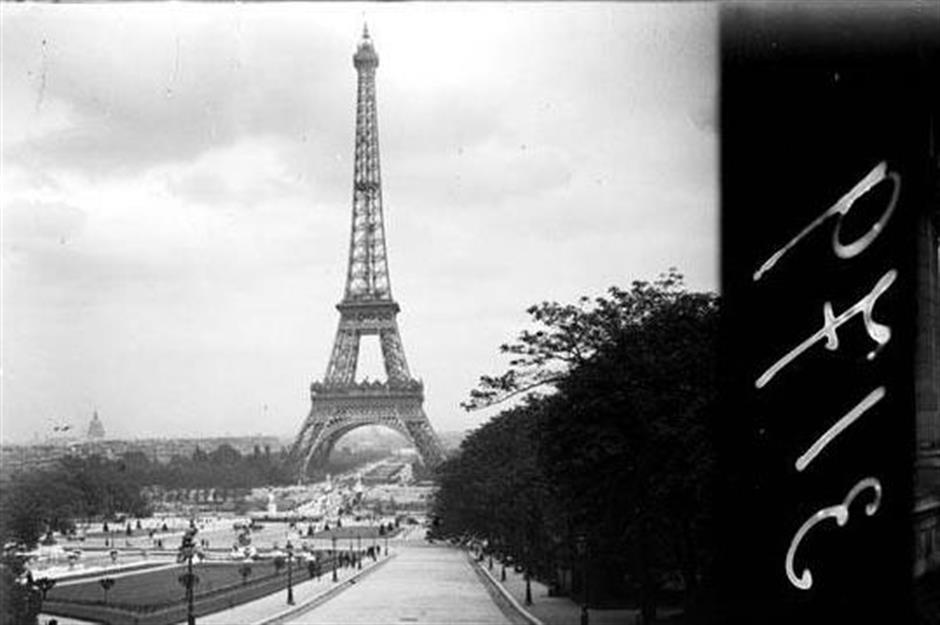

The Eiffel Tower scam

In 1925, with US police closing in, Lustig fled to Paris, where he would mount the most audacious con trick of all. It’s hard to imagine now, but at the time, the Eiffel Tower was a controversial landmark. Many saw it as an eyesore. Built for the 1889 World’s Fair and originally expected to last just 20 years, its demolition was an entirely plausible idea. Lustig saw an opportunity…

Setting himself up in an upmarket hotel suite with three accomplices, he claimed to be a government official charged with disposing of the landmark for scrap iron. He had forged letterheads printed and sent them to the city’s most prominent scrap merchants.

The letters explained that the government planned to sell the tower to the highest bidder. As the decision was controversial, absolute discretion was to be required. A series of secret meetings followed…

Wheeler dealer

One dealer in particular stood out. A relative newcomer in Paris, slightly unsure of himself and keen to make his mark, André Poisson saw the Eiffel Tower deal as his big break. Lustig groomed him to perfection, plying him with expensive meals and even taking him to a fake business meeting in Bordeaux.

According to Lustig biographer Christopher Sandford, Poisson paid 1,200,000 Francs, or the modern equivalent of around $5.3 million (£4.2m) for the tower. Even then, Lustig was not yet done with his victim. His coup de grace was asking the scrap dealer to pay a bribe on top to guarantee the bid. It added authenticity to his act as a lowly government official, and Poisson swallowed the bait.

That's how he came to pay yet another 70,000 Francs in cash – some $253,000 (£200k) in modern money. Lustig and his team fled to Vienna. They lay low, scanning the press for signs of a police investigation, but to no avail. Poisson was too embarrassed to report the crime.

A second towering deceit

As time went on and it became clear that nobody was looking for him over the Eiffel Tower swindle, Lustig reasoned that what he’d done once he could do again. Exactly as before, he and his accomplices assembled a group of scrap merchants willing to consider buying the tower. This time though, things didn’t go according to plan.

They did get an interested party who signed a contract, but then one of the unsuccessful dealers called in the police. It was time for Lustig to make a quick exit. He returned to America, but not before he’d pocketed the modern equivalent of over $300,000 (£230k) in a downpayment from the hapless would-be buyer.

Now setting up in Chicago, Lustig returned to his money box scam and other nefarious operations. Then, he pulled off a relatively small but hugely more dangerous trick…

Sponsored Content

Conning the mobster

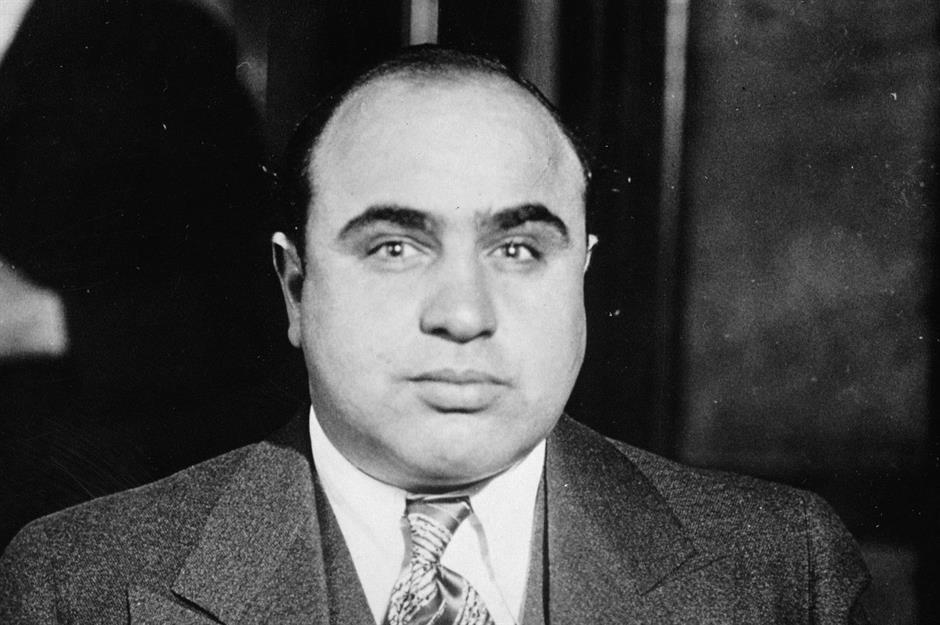

Victor Lustig stole from the great and the good but most of his targets were innocents with little awareness of the criminal mind. Not so his next one – the notorious Windy City gangster Al Capone.

Meeting at the Capone's hotel suite residence, Lustig persuaded him to invest $50,000 ($1.1m/£865k today) in a scam that he was planning. He promised to double the stake within 60 days. Capone handed over the money but made it clear what any double-dealing would mean – revealing a machine gun hidden in a recess behind the wall.

Lustig stashed the money away for the whole two months. Then he returned it to the mob leader, saying his plan had gone wrong, but he was nevertheless keen to repay the loan. Moved by what he thought was Lustig’s honesty, Capone let him keep $5,000 ($115k/£86k today), which is exactly what Lustig expected him to do all along. Fortunately for him, Capone never realised he’d been tricked.

Funny money

In 1930, Lustig expanded his business again, launching a counterfeit operation. He teamed up with a master forger named William Watts and together they set about making highly authentic banknotes, complete with a convincing security ribbon threaded through the paper.

Bravely (or perhaps recklessly), they did it in denominations that included $100 bills - the most carefully scrutinised of all. But the operation was a huge success; the couriers they employed weren’t even aware the cash was fake. Look at the picture – could you tell either?

In fact, it was too successful. There was so much forged money that the Secret Service worried it might undermine the real monetary system. As fake bills started to turn up all over the United States, they figured out who was behind it, but Lustig stayed one step ahead of them. Still, by now, he was a marked man.

Wanted

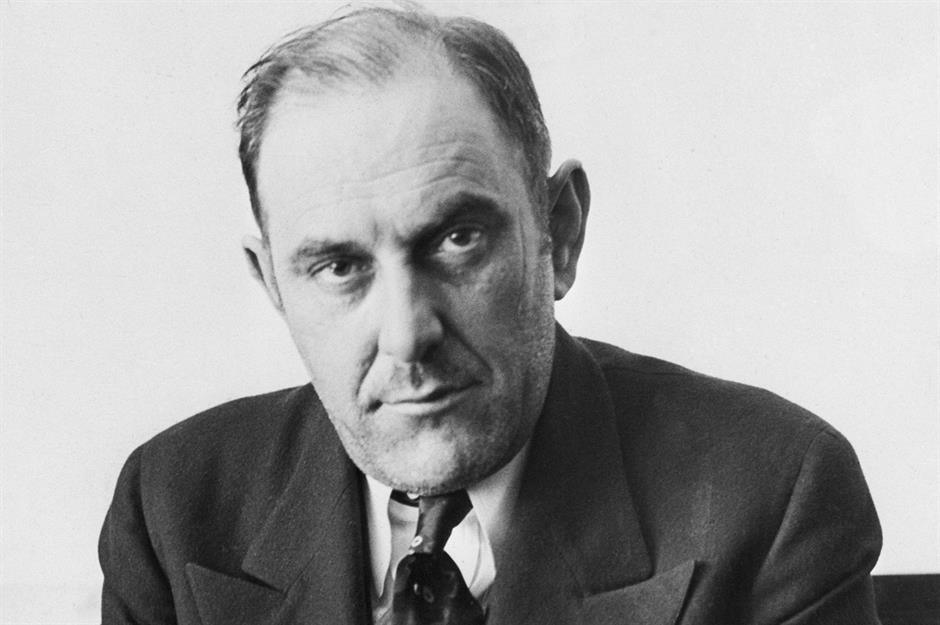

As Public Enemy Number One, the Feds were constantly on Lustig’s tail. One of their best agents, Peter Rubano (pictured, left, with Lustig centre), made it his personal mission to put him behind bars. He assembled a team of nine men who spent the next few years in a game of cat and mouse with the mercurial conman.

Catching him was no easy task. Lustig switched easily between many different disguises using costumes he carried in a trunk. One moment he could be a suave businessman; the next a rabbi or a priest. On one occasion he even swapped clothes and places with a blind beggar to evade detection. The pursuing cops dropped some change into his dish.

He was caught several times though, and in various US states, but somehow he always managed to trick, charm – or in some cases bribe – his way out of jail. By now he and Watts had begun producing counterfeit currency in almost industrial quantities, hoping to gain a fortune for their retirement.

Sponsored Content

Captured

_identification,_1931_(cropped) copy.jpg)

Lustig was undone, not by his criminal deeds but by his personal deception. By now, his first wife had divorced him but he had remarried and also continued his relationship with Billy Mae Scheible. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he was not an honest partner to either of them, and Scheible discovered he was dating yet another woman, the mistress of his forging accomplice. It’s thought that she made an anonymous call to the police and told them where he was staying in New York.

In the Spring of 1935, agents tracked him down. The first Lustig knew about it was the command "hands in the air". Ever the gentleman, he came quietly.

The agents found a key in his wallet that belonged to a locker at Times Square subway station. When they opened locker number 00099 they found $51,000 in counterfeit notes and the printing plates used to make it. That would be around $1.2 million (£945k) in today's money. Lustig was in trouble. Yet this was not to be the end of his story…

A daring escape

Pending trial, the authorities kept Lustig at Manhattan’s Federal Detention Center. It was supposedly a super safe federal penitentiary – not like the myriad small-town jails he’d wangled his way out of before. But he declared that no prison could hold him, and true enough, even this one was no match for the master manipulator.

During exercise time the day before his hearing, he picked the lock of a janitor’s storeroom, cut through the window mesh and secured a rope made from bedsheets knotted together. He then abseiled down to the street below, even pausing to rest on a windowsill, where, for the benefit of observers, he pretended to be a window cleaner, affecting a polishing action.

When he reached the ground, he gave a quick bow to those around him and vanished. In his cell he left a quotation from Les Misérables that invokes the need for honesty toward convicts, since “law was not made by God, and man can be wrong”.

The trial

Lustig was not free for long though. On the night of 28 September 1935, he ended up in a car chase with the Pittsburgh Secret Service. After nine blocks of dangerous neck-and-neck pursuit, the authorities locked their car’s wheels with his, sending both vehicles to a violent, crashing standstill. The cops drew their guns, ready to fire. Lustig calmly surrendered with the words, “well boys, here I am.”

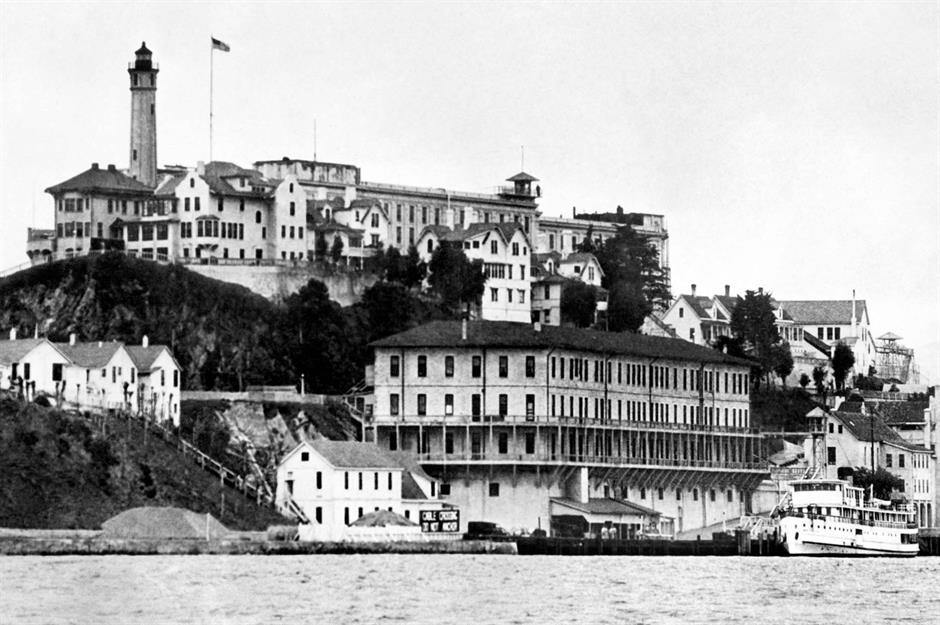

He was finally hauled before a judge and pleaded guilty to all charges. His sentence was 20 years’ incarceration at the newly opened Alcatraz prison island just off San Francisco. By now, his partner in crime William Watts had also been apprehended and stood trial beside him. Watts claimed to have printed some $5 million in fake banknotes, which if true would be over $90 million (£70m) today. The real amount may have been even higher.

In a photo of him leaving court after his sentence, Lustig (on the right) appears to be his old charming, polite and optimistic self. But he must have known that the game was up.

Sponsored Content

On The Rock

Lustig was charged and imprisoned under one of his many aliases: Robert V Miller. The court recorded him as unmarried and 44 years old. Led away to serve his time in March 1936, he vowed to escape again, but those watching said they didn’t believe it, and they thought he no longer did either. He was finally beaten.

As Inmate 300 at Alcatraz, Lustig was a relatively obedient prisoner, although the staff were constantly vigilant lest he get up to his old tricks again. When they asked if he would like to have a job in the prison, he asked if he could be a bookkeeper. And during his time on 'The Rock' he made more than 1,100 medical requests – on average, one every three days.

The prison staff assumed he was faking, but in 1947, his complaints proved genuine. He was transferred to a secure medical facility on the mainland where, on 11 March, he died from complications arising from pneumonia.

A Mystery to the end

Even in death, Lustig continued to fascinate America. A historian tried to track down his real life in Austria but could not find a single shred of evidence. It was as if he had never existed.

He died almost penniless despite the millions he’d scammed. But he left a non-financial legacy: a salutary lesson to law enforcement on the need to adopt more sophisticated techniques against fraud. To his fellow grifters, he even penned some rules for success. They include “always be a patient listener”; “never get drunk”; “agree with your target’s religious and political views” and “never boast”.

His cunning and agility mark him out as one of the 20th Century’s most interesting criminals. And though his misdeeds often ruined victims, it’s possible to admire him as an enterprising rogue. But he was still a rogue. Ironically, had he applied the same level of ingenuity to an honest life, he might have enjoyed an equally affluent and perhaps much longer life.

Now discover 13 infamous fraudsters who faked their way to a fortune

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature