America's empty ghost towns, and why they're abandoned today

The ghost towns that got left behind

St. Elmo, Colorado

A boom and bust in just 40 years, the town of St. Elmo got its official start in 1880. Then opportunities for gold and silver mining in the town saw a peak population of 2,000 just a decade later. Hotels, saloons and dancing halls soon opened, alongside a general store and telegraph office.

St. Elmo, Colorado

Sponsored Content

Rhyolite, Nevada

Rhyolite, Nevada

Bodie, California

Straight from the pages of a Western novel or the silver screen, Bodie had its heyday in the era of the California Gold Rush. The roots of the town began to grow in 1859 when a group of prospectors, inlcuding one named William S Bodey, found gold. But it was a few years later, after the establishment of a mill in 1861, that Bodie really became a place for people to call home. The town only really lasted five years, between 1877 to 1882, but in that time its population grew to more than 10,000.

Sponsored Content

Bodie, California

Bodie, which has more than 200 abandoned buildings, is now in the care of the California State Parks, which is quick to point out they are not restoring it, instead just preserving it in a state of “arrested decay”. The Bodie State Historic Park is open year round for visitors to explore the empty streets and peek through the windows of its saloons and other buildings, such as the coffin maker’s shop (pictured).

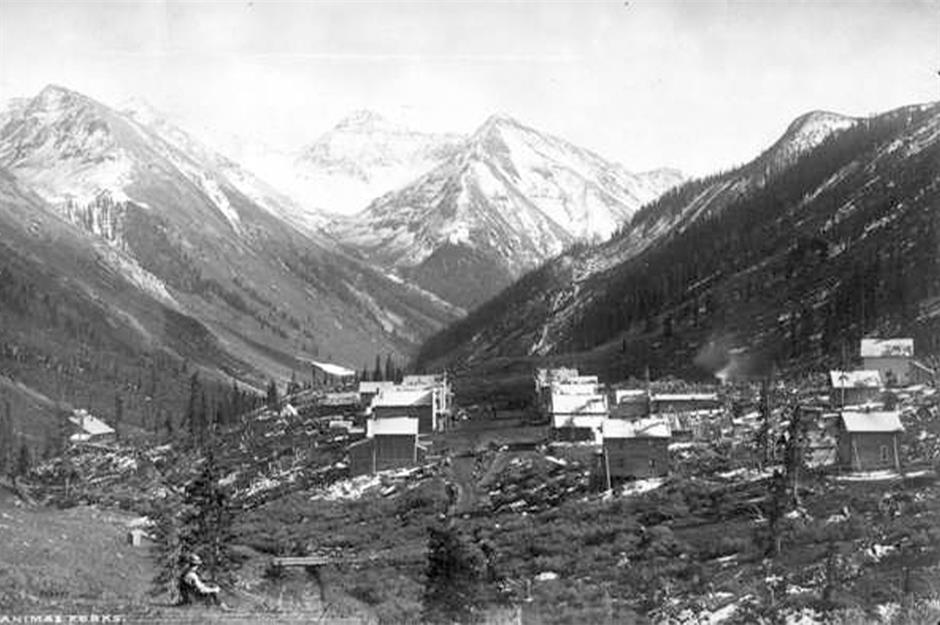

Animas Forks, Colorado

Animas Forks, Colorado

Sponsored Content

Garnet, Montana

The semi-precious red garnet stone is found in this area of Montana. However, it was actually gold that tempted prospectors and homesteaders to the area around the town of Garnet. It boomed and attracted as many as 1,000 residents with its four stores, four hotels, school, and 13 saloons. But when the gold ran out all the inhabitants abandoned it within 20 years. In 1912 nearly half the town burned down, and by 1940 Garnet was a ghost town.

Garnet, Montana

Shakespeare, New Mexico

In the 1850s Mexican Springs was just a stop for stagecoaches. That's until prospectors discovered silver in 1870, and the town grew to 3,000 people. The mines quickly depleted, but a rumor about diamonds being found in the area kept workers on. When it emerged that there weren't any, the population started to dwindle. A rebrand to Shakespeare and the launch of a new gold and silver mining company in 1879 brought brief respite.

Sponsored Content

Shakespeare, New Mexico

But the railroad would soon be built three miles away, kickstarting Shakespeare's second downfall, which was further exacerbated by the 1893 depression. The town was declared a National Historic Site in 1970 and, while privately owned, is available for guided tours. Billy the Kid and many more of history’s most notorious wild west characters called Shakespeare home, or at least spent time in its saloons. They are featured in occasional living history re-enactments.

South Pass, Wyoming

South Pass, Wyoming

Sponsored Content

Ashcroft, Colorado

Dating to 1880, prospectors put together this mining camp's courthouse and streets in the space of just two weeks. By 1883 Ashcroft was a town of approximately 2,000 people, with two newspapers, a school, sawmills, and 20 saloons. But just five years later it went bust. The Aspen Historical Society says: “Only a handful of aging, single men made Ashcroft their home by the turn of the century. They all owned mining claims, but spent their time hunting, fishing, reading and drinking in Dan McArthur’s bar.”

Ashcroft, Colorado

Kennecott, Alaska

Sponsored Content

Kennecott, Alaska

Gilman, Colorado

Gilman, Colorado

Sponsored Content

Rock Bluffs, Nebraska

Rock Bluffs, Nebraska

All that remains of Rock Bluffs is the school. Historians say the introduction of the railroad paved a path for the town’s demise, going through nearby Plattsmouth instead, as well as crossing the river on a bridge in Omaha. Now part of the Cass County Historical Society, visitors can see the school during open house events and children can visit for field trips. A recent fundraising campaign enabled the society to replace the school’s roof.

Verendrye, North Dakota

When Norwegian settlers arrived in the early 1900s, along with the railroad, they named their community Falsen. This rural outpost served as a vital stop on the line, providing river water for steam trains. The town adopted the name Verendrye instead in the 1920s, a nod to the 18th-century French explorer Pierre Gaultier De La Verendrye, who was the first European to visit the area. At this time Verendrye's homes and farms lacked electricity well into the Great Depression and residents started their own electricity cooperative in 1939, according to the Verendrye Electric Cooperative, which still exists today.

Sponsored Content

Verendrye, North Dakota

Glenrio, New Mexico/Texas

Glenrio, New Mexico/Texas

Sponsored Content

Rodney, Mississippi

Rodney, Mississippi

Cahawba, Alabama

Sponsored Content

Cahawba, Alabama

Down river from Mobile, Cahawba then became a distribution point for cotton, and construction of the railroad in the 1850s triggered a building boom. By the Civil War it had a population of more than 3,000. Unfortunately it was all downhill from there. The Confederate Army established a prison for 3,000 captured Union soldiers in the center of town. Then in 1865 a flood did actually inundate Cahawba and people began to leave. Many of the buildings have since been lost to fire or reclaimed by nature.

Ardmore, South Dakota

Ardmore, South Dakota

Sponsored Content

Batsto Village, New Jersey

European settlers set up the Batsto Iron Works along the Batsto River in 1766, which became useful during the Revolutionary War when it manufactured supplies for the Continental Army. Iron production declined and the factory would switch to glassmaking in the mid-19th century, but struggled nonetheless. Hundreds of people are said to have lived in the village during this time, which would eventually include a sawmill, gristmill (pictured), and general store.

Batsto Village, New Jersey

A Philadelphia businessman called Joseph Wharton purchased Batsto in 1876, as well as property in the surrounding area. He upgraded his mansion as well as other village buildings. From his death in 1909 until 1954 the properties were managed by a trust in Philadelphia. Then the state of New Jersey purchased the properties, allowing any remaining residents to stay in the village’s houses as long as they wanted. The last house was vacated in 1989.

Now meet America's biggest landowners

Centralia, Pennsylvania

Sponsored Content

Centralia, Pennsylvania

Picher, Oklahoma

Picher, Oklahoma

The Army Corps of Engineers reported in 2006 that more than 80% of the town’s buildings, including its school, were badly undermined and could collapse at any time. Two years later a tornado ripped through the town destroying buildings (pictured) and killing several residents. In 2009, the school district dissolved, the post office closed, and the government cancelled Picher's incorporated status. According to the latest data, which came from the 2010 Census, just 20 people lived in the town. There are no data available from the 2020 Census.

Sponsored Content

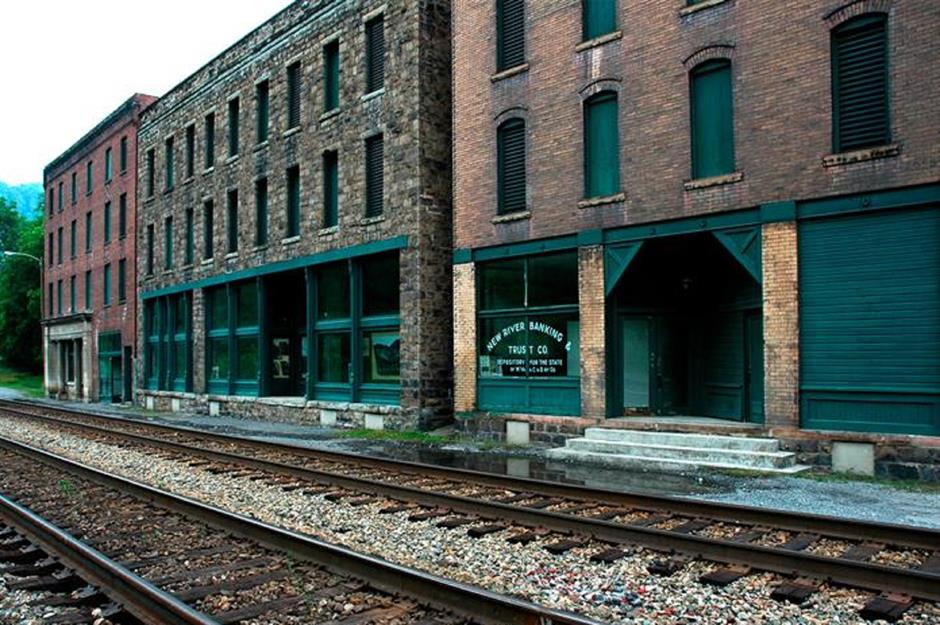

Thurmond, West Virginia

Thurmond, West Virginia

Road construction starting in 1917 was the beginning of the end. Then a series of devastating fires destroyed much of the town’s infrastructure in the 1920s to 1930s. The final blow to the rail industry in Thurmond came in 1949 when the C&O Company purchased its first diesel engine and began phasing out its steam engines. Most of the town is now owned by the National Park Service, and according to the 2020 Census the town is completely deserted.

Now take a look at America's rust belt cities that have reinvented themselves

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature