The shocking effect the pandemic will have on global poverty

Predicting the impact on global poverty

Anticipating exactly what the future has in store feels like an impossible task in these unprecedented and precarious times – what is clear however, is that the poor will be worst affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Click or scroll through to take a look at the shocking impact that the virus will likely have on the world’s most vulnerable.

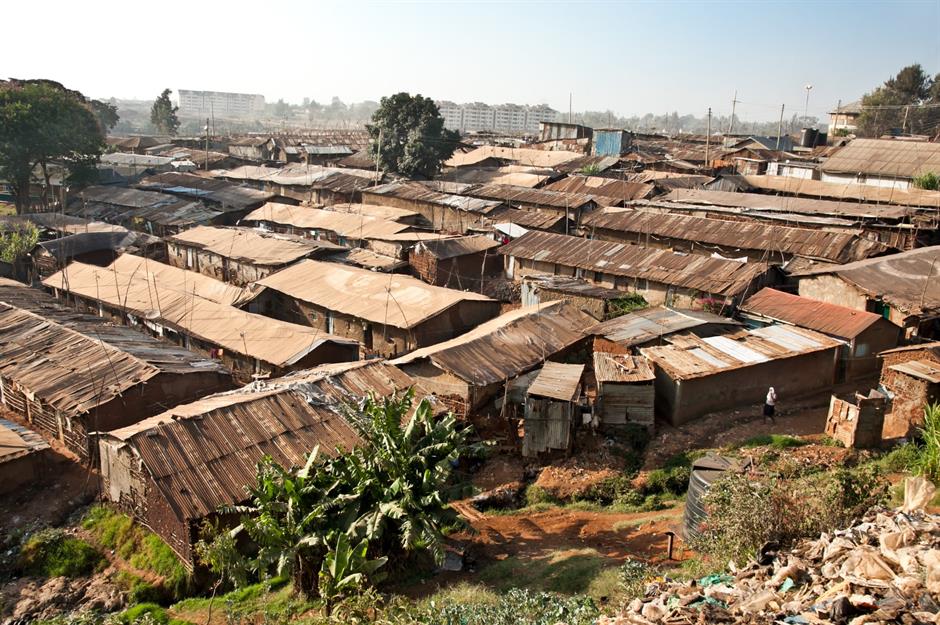

Extreme poverty is on the rise

Extreme poverty is defined as having to survive on a budget of just $1.90 (£1.50) per day, which has to cover everything from food and accommodation to emergency medical care. In 2019, 8.2% of the world’s population fell into that category – that’s 632 million people – and even before the coronavirus pandemic hit this was set to rise in 2020 to 8.6% of the world. That said, until now poverty had actually seen a decline in the last 30 years, and 2015 saw the level drop below 10% after the World Bank revised its parameters for what counts as “extreme poverty” from a daily budget of $1.25 (£1) to $1.90 (£1.50). Levels of extreme poverty are worst in Sub-Saharan Africa, followed by South Asia, and then countries in East Asia and the Pacific.

Virus-driven surge in poverty

Despite the fact that so far developing countries and regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa have been less affected by coronavirus in terms of health, these areas are set to feel the economic repercussions of the pandemic most harshly. Data from the World Bank predicts that the COVID-19 outbreak will push another 49 million people into the “extreme poverty” bracket, and that the areas worst affected by COVID-19 will be Sub-Saharan Africa, where 23 million people will be pushed into poverty, and South Asia, where 16 million will fall victim to the same fate.

Sponsored Content

Even developed countries have a poverty problem

Even countries with thriving economies struggle with poverty. In the US, 17.3 million people – 5.3% of the population – live in “deep poverty” according to Poverty USA, while 9.7 million Brits – 15% of the UK population – currently live in “absolute poverty”, according to House of Commons data. Sadly, the coronavirus pandemic is set to impact those living in these conditions the most.

Weaker economies will retract less, but end up worse off

In fact, "advanced economies" such as countries such as the US, the UK, Germany and Australia are set to see their economies hit harder than "emerging markets" and "developing countries". The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has predicted that on average, “advanced economies” will see a 6.1% retraction as a result of the pandemic, while Sub-Saharan Africa's developing economy is only set to fall by 1.6%, and other Low-Income Developing Countries' economies will have an average retraction of 1.4%.

Pandemic unemployment: government support in richer countries

Countries with stronger economies may see their economies suffer more due to the generous support schemes that they have put in place to help businesses and citizens who are unable to work through the pandemic. The UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak (pictured), announced that British companies can “furlough” their staff, a scheme where the government subsidises 80% of employees’ salaries (up to £2,500 – $3.1k – per month) and jobs are essentially put on hold until employees can safely return to work. In Germany, a similar system called “Kurzarbeit” covers 60% of lost net wages for those unable to work, and that goes up to 67% for those with children. Both schemes are designed to prevent companies folding and subsequent unemployment.

Sponsored Content

Pandemic unemployment: layoffs in richer countries

That said, unemployment is still rife, and as businesses have now suffered months of disrupted trade, many layoffs have already happened and are likely to continue. Studies have also shown that those with a low-income job are twice as likely to be made redundant, with industries such as travel and hospitality, which have high proportions of lower paid workers, being hit particularly badly. In the US, despite the $2 trillion (£1.6trn) CARES Act (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) package which includes the offer of one-off payments of up to $1,200 (£968) to individuals impacted by the pandemic, nearly 40 million Americans are now seeking unemployment benefits, which is almost a quarter of the US workforce. The country hasn't seen this level of disruption to the job market since the Great Recession.

Now read: Coronavirus, how job losses compare across the world

Pandemic unemployment: migrant workers sending money home

Across the world, one in nine people are supported by money sent by migrant workers, according to the United Nations (UN). Global remittances reached $689 billion (£560bn) in 2018, and $528 billion (£429bn) of that is believed to have gone to developing countries, according to the World Bank. Although workers typically only send around 15% of their earnings, it is a vital lifeline that families rely upon and so if those workers become unemployed during the pandemic, that chain of support is cut off. Lockdown has also forced millions of migrant workers in cities like New Delhi, India (pictured) to return to their native villages after their work was suspended. While those who are still able to work through the restrictions have faced additional difficulties in getting their money home, as many bank and money transfer systems have been impacted by the coronavirus outbreak.

Pandemic unemployment: daily wagers fear starvation

Daily wage work is a common source of income across South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, but if the family breadwinners don’t go to work one day, that’s a day that that household will go without money. The informal economy doesn’t have support systems that families can rely upon now that much of that work has dried up, and for many in countries like India, there is a greater fear of starvation than coronavirus.

Sponsored Content

Food crisis: poor countries are starving

Starvation is not a new problem, and on average 21,000 people were dying of hunger every single day before the pandemic. The number of people suffering from “acute hunger” was already at 135 million in 2019, but the UN has forecasted that a further 130 million people will find themselves on the verge of starvation as a result of COVID-19. And those who don’t die of hunger are more susceptible to the virus, as malnutrition will have compromised their health.

Food crisis: rich countries struggle to find balance

Rich countries have seen both a depletion and surplus of food across different settings. In countries such as the US and UK there has been an increased reliance on food banks and similar charities by the poorer in society, but richer countries have also faced the issue of having too much produce that they are unable to sell. Dutch farmers have been left with one million tonnes of excess potatoes, British dairy farmers have poured away thousands of litres of unwanted milk, and farmers across the US have had to consider “de-populating” their farms, as they’ve been unable to shift livestock that is costly to keep. This is a striking example of how coronavirus is a universal problem, but its implications vary wildly depending on different financial situations.

Food crisis: the future of food production and distribution

Food production and distribution in developing countries already had threats to contend with pre-virus: droughts worsened by climate change, the lingering aftermath of the Great Recession, and hordes of locusts were all vying to push hunger-stricken countries into deeper levels of poverty. Coronavirus has further disrupted already unstable supply chains, and another recession has been pre-empted by economists. Countries looking to protect their own people first may resort to protectionist tactics like increasing tariffs, changing quotas, and implementing administrative barriers, all of which drive up prices for countries importing their food. Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, is the world’s largest rice-importing region, and such measures would prove most damaging for those with no money to spare.

Sponsored Content

Foreign aid: countries looking after their own

This hoarding of resources also applies to money. As countries sink into economic crisis – as is starting to happen right now – history shows that foreign aid spending patterns change. As individual donors and governments look to save money, sending funds abroad may become less of a priority. Together, 193 countries have signed an agreement to end world hunger by the end of this decade, which is estimated to cost between $7 billion and $265 billion (£5.7bn-£214.7bn) each year until then. Can that ambitious target be reached as more people are pushed into poverty, while the number of people willing or able to help may decrease?

Foreign aid: coronavirus is making refugee camps more dangerous

Among those people in desperate need of foreign aid are those living in refugee camps. Although COVID-19 has meant that media attention has largely moved on the refugee emergency, it is still very much bubbling away, with coronavirus adding another layer of tribulation to those already living in crisis. The staple preventative measures needed to stop the spread of the virus – regular hand washing and social distancing – are an impossibility for those living in overcrowded and ill-equipped camps.

Foreign aid: refugee camps could lead to the pandemic's biggest loss

The infamous Moria Camp (pictured) in Greece for example was built to house 3,100 people, but its population has since sprawled to over 20,000. On-site medical facilities are stretched to capacity in normal times, let alone during a global pandemic, and they are almost entirely reliant on volunteers. There are currently 2.6 million refugees placed in this kind of temporary accommodation, and confirmed and suspected cases of coronavirus have been reported in camps around the world. If allowed to get out of hand – which is all too possible given the living conditions – these outbreaks could lead to the greatest loss of life the pandemic has seen.

Sponsored Content

Healthcare: countries in crisis aren’t coronavirus-ready

Official camps are undoubtedly a bleak place to wait out the pandemic, but many refugees still consider themselves lucky as they have escaped their war-torn home countries. But in terms of healthcare facilities, neither option is prepared to deal with a pandemic. In the entirety of Syria, only 64% of hospitals are considered to be “fully-functioning” (pictured). The Central African Republic has a total of three ventilators to serve a population of 4.7 million, while in the case of a widespread outbreak in South Sudan, 11.2 million people would be reliant on only 24 ICU beds and four ventilators, according to data from the International Rescue Committee. These are not isolated cases of only a few countries that aren’t ready to deal with a pandemic, but rather a pattern of failing healthcare systems seen across all countries that exist in poverty.

Healthcare: deadly diseases already in circulation

Many areas that are most susceptible to COVID-19, like sub-Saharan Africa, are still ravaged by illnesses that have been all but eradicated in developed countries. Tuberculosis killed 417,000 people in Africa in 2016, and the World Health Organisation (WHO) has been forecasting a meningitis outbreak since 2015, as cycles of the disease hit every five to 12 years. Malaria and HIV are also among the biggest killers in Africa, while so-called “lifestyle diseases” such as diabetes, cancer, and various respiratory illnesses are on the rise too. So far, the World Bank has put aside $12 billion (£9.8bn) to develop healthcare facilities in low- and middle-income nations, and the IMF has made $50 billion (£40.8bn) available to assist developing markets during the coronavirus crisis. These are enormous sums of money, but given the sheer scale of the healthcare problem across developing countries, it is yet to be seen how much of an impact they will have.

Healthcare: battle for a vaccine

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the deaths caused by these diseases is that vaccines, or at least effective treatments, that could have prevented them are in existence. Pharmaceutical companies in the world’s leading economies are scrambling to find both cures and preventative drugs for COVID-19, but with struggling economies still not having vaccinated their populations against diseases such as tuberculosis and meningitis, there are fears that poorer nations may miss out on any potential coronavirus vaccine or treatments. Medicine can quickly become a chess piece for the rich rather than a resource for general public health, as was seen in 2015 when hedge fund manager Martin Shkreli bought the manufacturing license for AIDS/HIV drug Daraprim, and hiked up the price per dose from $13.50 (£11) to $750 (£610).

Sponsored Content

Healthcare: vulnerable more at risk

While the world awaits a vaccine, rich countries aren't able to guarantee the good health of their citizens. In 2018, 27.5 million Americans didn’t have health insurance and based on those figures, 8.5% of the US population are living through a pandemic with no means of seeking affordable medical attention. Even in the UK, where the National Health Service (NHS) provides free healthcare, those who are financially worse-off have a much higher chance of dying from the virus. There are more than twice as many deaths from COVID-19 in poorer regions than in affluent areas, according to data by the UK's Office for National Statistics. There are pre-existing health problems that can worsen the effects of COVID-19, but experts have suggested that inequality is the main underlying condition causing people to die from coronavirus.

Read more about the countries with the best value healthcare in the world

Healthcare: a looming mental health crisis

Most coronavirus news bulletins are punctuated with case numbers and death tolls, but the impact COVID-19 is having on mental health is also of great concern among experts. The psychological burden of living through a pandemic is immense, which is only exacerbated by side-effects triggered by lockdown, such as longer periods of isolation and increased cases of domestic violence. As countries struggle to keep the physical health of their people afloat, the cost of the imminent mental health crisis is likely to be high. Not only that, but poverty is a known cause and effect of poor mental health and as the economic effects of the pandemic take hold, the mental health of those impacted is only set to get worse.

Education: lack of education causes poverty

Another factor in the vicious cycle of poverty is a lack of education, and before the pandemic there were more than 72 million children of primary school age who are “unschooled”, according to children’s rights NGO Humanium. As a necessary measure to prevent the spread of COVID-19, schools across the globe have been forced to shut, pulling a further 810 million children in low- to medium-income countries out of the education system for an infedinite period of time. This doesn’t only come at the cost of missed classes however, as for many deprived children school provides their main, or only, meal of the day. This further adds to the issue of global hunger and its detrimental effects on health.

Sponsored Content

Education: technology has the potential to save the day

Right now, many of the world’s children are being educated virtually. However, this is a privilege extended only to those with internet access, which is a luxury that many cannot afford, even in richer countries. In April, it emerged that there were over nine million pupils in the US who wouldn’t be able to log on for their classes due to lack of internet connection. E-learning has only highlighted the gap between rich and poor when it comes to education – this is something that charities like Save the Children are looking to fix by providing necessary learning materials, but there’s no guarantee that aid is reaching those who need it most.

Education: knock-on effects are worse than the disease itself

The aftermath of previous health crises can help us to predict possible knock-on effects of taking children out of school, and the outlook isn’t positive. The outbreak of Ebola between 2014 and 2016 for example caused 4,000 deaths in Sierra Leone in West Africa, but that number was lower than the number of deaths caused by childbirth complications in girls who had become pregnant, as teen pregnancies shot up following school closures. Coronavirus is a different disease to Ebola, but removing children from school to protect their wellbeing could lead to equally dangerous consequences in the outside world.

Social mobility is at risk

These factors all play into, and worsen, the Catch-22 nature of poverty across the world. Poverty causes poor nutrition and healthcare, meaning that those living in such conditions are at greater risk of falling victim to coronavirus. Those aspects in turn lessen the chances of children getting an education and finding safe and reliable employment, and the pattern repeats again and again. Other countries can provide financial support, but as discussed the global nature of the pandemic may mean that foreign aid is not as forthcoming as during other humanitarian crises.

Sponsored Content

The future of global poverty

The UN wants to have made significant steps in tackling poverty by 2030, with the goal that fewer than 3% of the world will be living on $1.90 (£1.50) a day in 10 years’ time. Global poverty rates had gone down by more than half since 2000, which shows great progress so far, but new projections factoring in the coronavirus pandemic tell a very different story. Experts now believe levels of poverty could rise to those last seen in 1990, effectively eradicating 30 years’ worth of hard work. While this is a worst-case scenario forecast, that is only likely to affect the worst-hit regions, it shows that the coronavirus pandemic will continue to have a detrimental impact on those in poverty for years to come.

Now read about how the world bounced back from the last global pandemic

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature